Education Indian music: hindustani music practice rhythmic cycles riyaaz tala theka

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Understanding Tala – Internalizing Talas and Thekas

A thread on rec.music.indian.classical (USENET) attracted my attention today.

It started with a request:

“I am learning ICM at my own and also attending community school once in a week. I have following question when I tried to practice at home.”

1) In Teen Taal (16 Beats) From which beat the composition/bandish/alaap etc. starts ? i.e. should I start from Taali or Khali which beat #. ( I am using Radel DigiTaalmala)

2)Is there any book available to teach me the basic concept of starting composition with any Taala ? (means which will show me that in “xyz” taal – the composition will start from taali or khali or 3

or 4th beat etc.)Your advice/response will be highly appreciated.

With Kind Regards

Chandrakant

I responded as follows, in what strikes me as a pretty good summary of the advice I am frequently giving my students about working with theka:

There are two different issues at play here.

One is to understand the internal structure of the tala.

To do this it is very useful for a vocalist to practice theka

recitation. Note the relationships of the tabla bols to the tongue

and laryngeal position.All important right hand strokes use unvoiced dental “t” sounds: ta,

tin, tun tet. Na is the anusvar of that tongue position. Recite “ta

tin tin ta” over and over; experience the difference in overtone

structure between the “a” vowel and the “in” phoneme as each is

triggered by the “t” tongue attack.All important left hand strokes use the velar consonants. Ge and

Kat. Ge is a voiced velar that is sustained on an “e” vowel, Kat

begins with an unvoiced velar and ends with a retroflex “T” stop.Recite “Ge Ge Ge Ge Kat Kat Kat Kat” over and over, experiencing the difference between the voiced sustained and the unvoiced stopped velars.

But what of strokes that use both hands? Discover for yourself that

it is impossible to say “Ta” and “Ge” simultaneously. Try it; your

tongue won’t be able to do it.So how to speak the syllables for these strokes? Simple. Change the unvoiced dentals of the right hand to voiced dentals: ta + ge = dha; tin + ge = dhin, etc. Recite “Dha Dhin Dhin Dha” and feel that there is sonic activity taking place in two places in your vocal mechanism. Your vocal chords are making a steady stream of impulses (basically “uh uh uh uh uh uh” since shaping vowels is done by the mouth), and your tongue is articulating lightly between your teeth (“ta tin tin ta” etc.). The front of your mouth is the high drum, your throat is

the low drum.Now recite theka for a long time, and experience the rise and fall of impulses in your throat and mouth as you move through the cycle. Pay particular attention to the return of your vocal chords on the 14th matra, emphasize “dhin dhin Dha DHA” — that’s the sam.

In order to understand the relationship between the bandish and the theka, it is very useful to recite theka while listening to vocal recordings. In this you want to have standard professional accompanists; attempting to recite theka while Zakir is embellishing is much more difficult. On many older recordings, tabla is very low in the mix. I often tell my students to listen to someone like Veena Sahasrabuddhe as her recordings are generally mixed very well and the tabla players are people like Omkar Gulwady, who keep beautifully flowing theka without much finger-chatter.

Listen to many different bandishes while you recite. Observe the many different ways they have of coming to the sam and maintaining a relationship with it.

A useful exercise is (once you know where the sam is located on a

particular bandish) to sing one line of the chiz, then recite theka

*from the point in the cycle where the song begins*. Thus, an 8-beat mukhda would start on khali; one would sing the song text once, then recite, starting at khali: “Jabse tumhi sanga LAagali / Dha tin tin ta ta dhin dhin dha DHA dhin dhin dha dha dhin dhin dha / Jabse tumhi sanga laagali / Dha tin tin ta ta dhin dhin dha DHA, etc., etc.” A five-beat mukhda, on the other hand, might yield something like “Bolana LAAgi koyaliyaa / ta ta dhin dhin dha DHA dhin dhin dha dha dhin dhin dha dha tin tin / bolana LAAgi koyaliya / ta ta dhin dhin dha DHA, etc., etc.”Practice these approaches assiduously and enthusiastically and you will gain many interesting rhythmic insights.

Warren

Indian music music photoblogging: Bhopa Jaisalmer Rajasthan ravanhatta

by Warren

8 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Rajasthani Music: Tulcharam Bhopa plays Ravanhatta

In 2000, Vijaya and I traveled to Rajasthan, staying in Udaipur and Jaisalmer. I have loved Rajasthani music from the first time I heard it, and it was really a treat to listen to traditional artists in both cities.

The Ravanhatta (wiki spells it ravanahatha) is one of the oldest bowed instruments in the world.

The bowl is made of cut coconut shell, the mouth of which is covered with goat hide. A dandi, made of bamboo is attached to this shell. The principal strings are two: one of steel and the other of a set of horsehair. The long bow has jingle bells.[1]

The artists come from a lineage of bards, the Bhopas:

Every prominent family of the land-holding Rajput caste, I discovered, inherited a family of oral genealogists, musicians and praise singers, who celebrated the family’s lineage and deeds.

(snip)

…unlike the ancient epics of Europe – the Iliad, the Odyssey, Beowulf and The Song of Roland – which were now the province only of academics and literature classes, the oral epics of Rajasthan were still alive, preserved by a caste of wandering bhopas who travelled from village to village, staging performances.

Some Bhopas, of course, make their living performing for tourists. There were three or four ravanhatta players on the cobbled walkway up to the Jaisalmer Fort. We listened briefly to each; the one who really stood out to our ears was Tulcharam Bhopa, and we recorded a few of his pieces. It was early evening of Indian Independence Day, August 15, 2000.

Here are some of our photographs of Jaisalmer accompanying the beautiful playing of Tulcharam Bhopa, whom I’m told died a few years ago.

Education Indian music music: intonation khyal learning practice riyaaz singing

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Practice Tips and Techniques, No. 1

About ten years ago my student Brian O’Neill and I had a long discussion about practice techniques. He transcribed it and sent it along to me, and it languished on my hard drive. Recently, I remembered the material and dug it out. It needs editing, so it’s going to take a while to get it all tidy, but there’s some worthwhile stuff in that document. The first part of the conversation was about practicing the drone — the most basic type of self-tuning a singer can do.

WS: When I started out I did not have any particular deep sense of discipline in practice. Eventually I began by starting every day with a drone session. I would just sing the tonic, the Sa. And I would focus on that, and I would…

BTO: Tune up?

WS: Yeah. You try & get your temporomandibular joint a little bit loose; you do a little bit of overtoning; some tongue stretches; try and make sure the soft palate is down and you’re getting sinus resonance. What I tell my students is to begin with a little session (it might be 10 minutes) of Sa, every morning. And when you do that, you examine different variations.

For example, subtle intonational shifts. Get on Sa and move the note the smallest possible amount flat, then return it to the center, then move it sharp and return it. What you’re really doing is, you’re decreasing the intonational standard deviation of the pitch.

So that’s one approach to the Sa.

Another approach is breath control. You get a watch with a sweep second hand, sing Sa [one breath’s worth], and time yourself. “Hmmm, that was 11 seconds. OK, I’m going to go for 12.” And then you ask yourself, “Where does most of the air go out? Oh, most of the air goes out in the very first half a second. OK, let me try and regulate that. Good!, I got 5 more seconds on that.” So those are all good ways of occupying yourself on the drone. So 10 minutes turns out to be nowhere near enough time, and you just pick one or another of those exercises to do with the tonic.

There’s a lot more to come, including very specific methods for organizing your practice to get the most effective study in the time you have available. Stay tuned!

Finally, a word on a related subject.

If you’re studying or teaching music, you’re engaged in the long, slow, work of taking parts of our past and preparing them to travel into the future.

Therefore, you owe it to yourself and to the music you cherish — to educate yourself about climate change.

No stable climate – no music. It’s as simple as that.

MUSIC IS A CLIMATE ISSUE

Indian music music photoblogging: Bhimsen Joshi Gangubai Hangal khyal Kumar Gandharva Malini Rajurkar Mallikarjun Mansur

by Warren

1 comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Khyal Photoblogging

These were taken between 1985 and 1987, at various concerts in Pune, Mumbai, Miraj and Delhi. Enjoy:

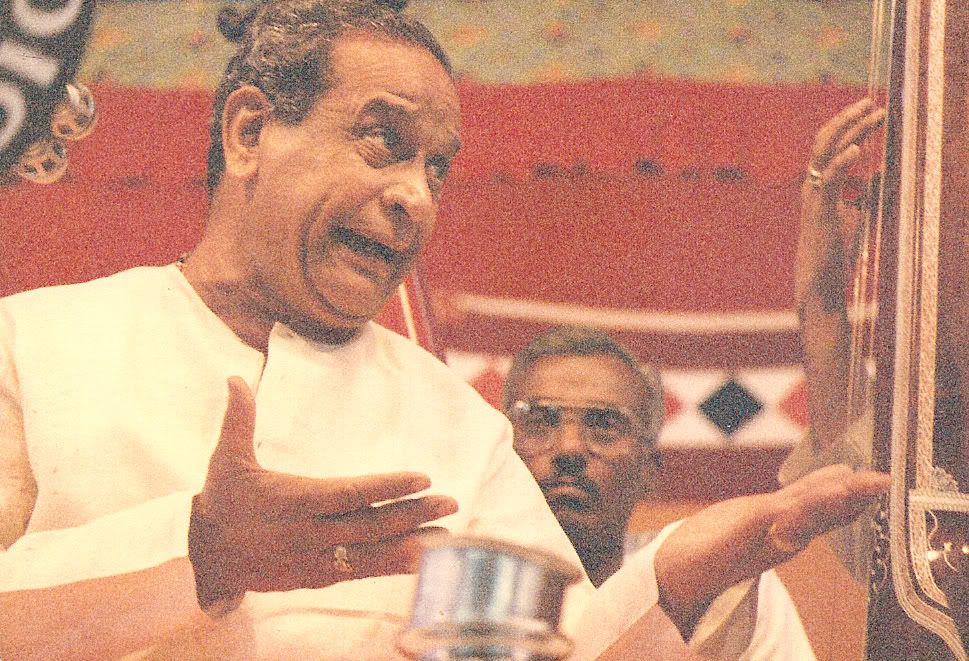

Bhimsen Joshi:

Sawai Gandharva Mahotsav, 1985. He was singing a beautiful Todi, “Changai nainawa” followed by “Langara kankariyaa jina maaro.” Nana Muley on tabla, Purushottam Wallawalkar on harmonium.

Indian music October 24 Action photoblogging: Dance Indian dance photoblogging

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

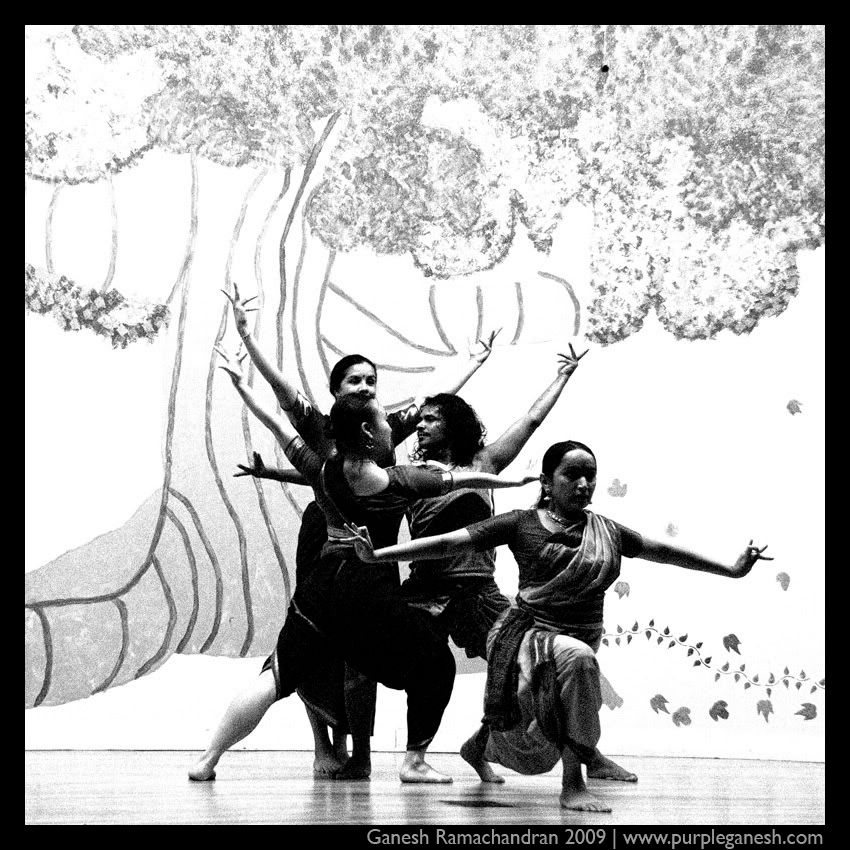

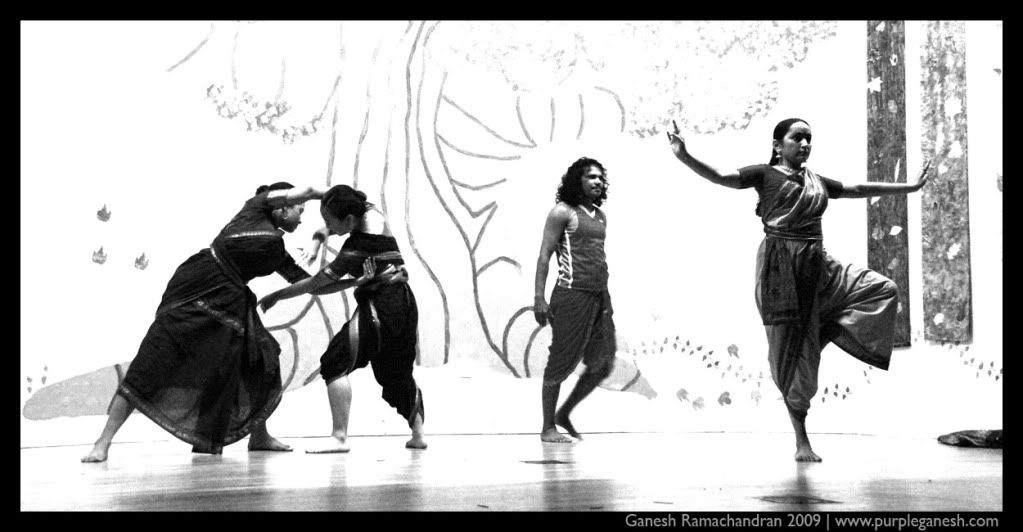

Aparna Sindhoor Dance Theater: New Photos

Ganesh Ramachandran took these photographs of the Aparna Sindhoor Dance Theater during the “Playing for the Planet” concert. I think they’re terrific.

environment Indian music music October 24 Action Warren's music: Gorakh Kalyan khyal Raga

by Warren

4 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Playing for the Planet: Warren Senders’ set

When I first got the idea for the “Playing for the Planet” concert, I knew instantly that I wanted to sing these three compositions in Raga Gorakh Kalyan. I will update later on with the complete text and meaning; tonight I just want to get this posted before I go to sleep.

environment Indian music October 24 Action: Dance Indian dance

by Warren

1 comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Playing For The Planet: Aparna Sindhoor’s Set

The fifth ensemble to perform (starting at around 9:20 pm) was the Aparna Sindhoor Dance Theater. The room lighting was wretched; even with the videocam on “nightshot” setting there was a lot of detail lost. But nevertheless, the power and genius of Aparna and her ensemble are evident in this video. This is a 25-minute excerpt from their long piece, “The Story and The Song,” about a young woman who could turn herself into a flowering tree and the prince who fell in love with her. The fact that there was a giant painted tree as a backdrop was purely serendipitous.

Here are four photographs (courtesy Hadley Langosey) and video (courtesy the Sony Cam mounted on a tripod, on top of the piano in the back of the room.). The first few seconds of the introduction were lost, but the rest of the performance is intact.

Indian music music: 78s Gwalior gharana khyal Ramakrishnabua Vaze

by Warren

5 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

A Blast from the Past: Ramakrishnabua Vaze (1871-1945)

One of the greatest voices of pre-Independence India, Pt. Ramakrishnabua Vaze was born in 1871:

…in a small village in Maharashtra…Vaze Bua lost his father soon after and was brought up by his mother. He studied for only a few years in school, his passion for music overtaking his interest in studies. With his mother’s help, he spent the next few years, moving around, taking lessons in music from several teachers. He was twelve when he was summoned home to get married and take up his duties as a householder. The newly married Vaze felt it improper to depend upon his mother for financial support and decided to take off on foot, with no particular destination and only the pursuit of music on his in mind.

Link

Note that at age twelve, he decided it was improper to depend on his mother…so he presumably left his wife (who was presumably even younger) at home and went out a-wandering.

At the time, all roads led to Gwalior, where the young man eventually became a disciple of Ustad Nissar Hussain Khan (note: this is not the Nissar Hussain Khan of Rampur-Sahaswan fame). The typical spate of privations, indignities and unswerving dedication eventually led to a level of musicianship and artistry that continues to amaze and inspire.

“His performances were always lively and intellectually stimulating. His layakari was flawless , his taans had clarity and force and he would leave his audience spellbound. He was responsible for bringing many little known ragas to light and as a composer, his specialty was bandishes in fast tempo.” Link

Here are a few of Vazebua’s wonderful short recordings, made during the heyday of 78 rpm discs in India. I’ll add more as I get around to it.

Enjoy!

Indian music music: Anant Manohar Joshi Gwalior gharana Indian music khyal music musical history

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

A Blast from the Past: Anant Manohar Joshi (1881-1967)

Here are four short performances by Pandit Anant Manohar Joshi, also called “Antubuwa.” Disciple of Balakrishnabua Ichalkaranjikar and “Bhugandharva” Ustad Rahmat Khan. Guru of Dr. S.N. Ratanjankar; father and guru of Pandit Gajananrao Joshi. Anant Manohar Joshi was born in Kinhai village, March 8, 1881. His father Manoharbuwa had learned classical styles from Raojibuwa Gogte of Ichalkaranji, and became a court musician at Aundh. He died when Anant was seven. Antubuwa became one of the top-most performers of traditional Gwalior style khyal, although he never achieved the fame of his guru-bhai, Vishnu Digambar Paluskar. “A powerful voice, daanedaar taans, and clear pronunciation of words characterised his rich and systematic style” according to Susheela Mishra (“Some Immortals of Hindustani Music”). He died in Bombay on September 12, 1967.

These short performances show Antubuwa at the end of his career. His voice is no longer flexible and his intonation is somewhat coarse, but the vigorous spirit remains.

Indian music music: India photoblogging travelogue

by Warren

14 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Musical Journeys in India: An Audio Travelogue

I must have been eight or nine when my Uncle Russell began taking me, once a month, to a lecture series at the university where he taught; each month a different world traveler would do a grownup version of show & tell. Slides, movies, anecdotes, facts. Exciting? I loved those outings, and I wish I remember more. But they certainly made their impression: as a boy, I knew that I wanted to travel, to see at least a few of those places first hand. Uncle Russ’ career as a management consultant for the Ford Foundation had taken him and his family to live in places far from the Boston suburbs where I grew up. One of those places was Hyderabad, India, and the souvenirs he and my aunt brought back from their years there were my first introduction to Indian culture.

I was seventeen when I encountered Indian music, and from the moment my ears opened to the sound of Hindustani ragas, I knew that this was something I had to do. Over the years that followed, I collected LPs and cassettes of Indian music with zeal; by the time I actually went to India, I had steeped myself obsessively in its classical and vernacular music. Now, thirty years later, I’ve got some show & tell of my own.