Education Indian music music: muscle training practice rhythmic cycles riyaaz tabla

by Warren

9 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Practicing Inside Rhythmic Cycles

One of the most challenging areas for many students of Hindustani music is working within rhythmic cycles. The ready availability of tabla machines has not solved this problem, because the core issue has more to do with not knowing how to practice than with not having a tabla player available all the time.

It is helpful to spend some time analyzing the various components of rhythmic-cycle practice. Once a singer begins this work, the cognitive load goes waaaaaay up; a lot more brain cells are required to keep all the elements of the musical equation under control. While holistic, gestalt-oriented practice is a must, it can be very helpful to break things down into smaller components and approach them with reductionistic ruthlessness.

To be competent in rhythmic-cycle-based improvisation, a singer must:

1 – be able to process rhythmic information concurrently with intonational information. That is to say, you have to be able to hear and feel the beats without getting distracted by them to the point that you go out of tune.

2 – be able to recognize important beats in the cycle and recalibrate according to position. That is, you have to hear crucial structural points and have enough cognitive strength available to lengthen or shorten your melodic line if necessary.

3 – be able to make coherent melodic shapes of specific lengths. In performance, it’s not enough to start an improvised melody at a specific point in the rhythm and finish it at another point — the melody you’re making needs to make sense. And (as if that weren’t enough) it needs to make sense at several levels; it has to be correct in raga terms, and it has to have gestural integrity. Those two are emphatically not the same thing.

Let’s take those distinct skills in turn, and I’ll discuss some ways of approaching them in the course of your practice.

India Indian music music: 78s old masters Ramakrishnabua Vaze

by Warren

1 comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

More Music from Ramakrishnabua Vaze

Here are three more of the classic 78 rpm discs recorded by Pandit Ramakrishna Vaze (1871 – 1945). At some point soon I will post the long version of his Miyan ki Malhar, a classic recording from the AIR archives; it’s longer than the maximum allowed by YouTube, so I’ll be using Vimeo for that one.

The complex compound raga Khat

Deodhar tells some amusing stories of Vazebua’s eccentricity:

“In 1927 I requested Buwasaheb to pay a visit to my music school. He appeared in a loose shirt and haphazardly torn cap…Some of our boys and girls sang for him. After this I requested him to say a few words to the students. He started his address with these words, ‘I am a simple person. I do not like to dress up. I have a jacket — I even wear it sometimes. I say, Mr. Deodhar, come to my house and I shall show you my jacket. Very beautiful material. One cannot acquire learning by putting on fine clothes — can one now?’ Some of our girls could not help laughing at this. They put their hankies to their lips and giggled. I felt embarrassed. IN an attempt to change the subject I told Buwasaheb that our students were anxious to hear him sing…He duly appeared at the school as promised, and sang beautifully for our students.

(snip)

“Shri Korgavkar…decided to start a harmonium class in Belgaum…he sent a most courteous invitation to Vazebuwa to preside over the inauguration function. Vazebuwa agreed….Buwasaheb was requested to give his presidential address. Buwasaheb stood up. The audience was all attention. Buwasaheb started, ‘Friends…friends.’ But he was at a loss to find anything more to say. After an embarrassingly long silence he said, ‘Nothing…nothing,’ and sat down. After repeated clamour from the audience and entreaties from the organizers, Buwasaheb once again stood up and continued his speech, ‘Ladies and Gentlemen! Today we are inaugurating this harmonium class. This instrument is known as a harmonium. We call it bend-baja (a derogatory term usually associated with a mouth-organ). So from today anyone who wants to learn to play bend-baja can do so.’

B.R. Deodhar: “Pillars of Hindustani Music,” pp. 128-130

India Indian music music: Amir Khan genius

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Ustad Amir Khan

Because everybody should fall in love with a voice, and Amir Khan’s has filled my ears for over three decades now.

Raga Malkauns

Raga Todi

Raga Yaman

India Indian music music photoblogging: Amjad Ali Khan Hindustani instrumentalists Shahid Parvez Shivkumar Sharma Sultan Khan Zakir Hussain Zarin Daruwalla

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Hindustani Instrumental Photoblogging

As part of my continuing drive to provide visual, auditory and intellectual content, here is an assortment of the photographs I took of Hindustani instrumentalists during the 1980s. Zakir was performing a great deal in Pune during that time, and I got many good images of him.

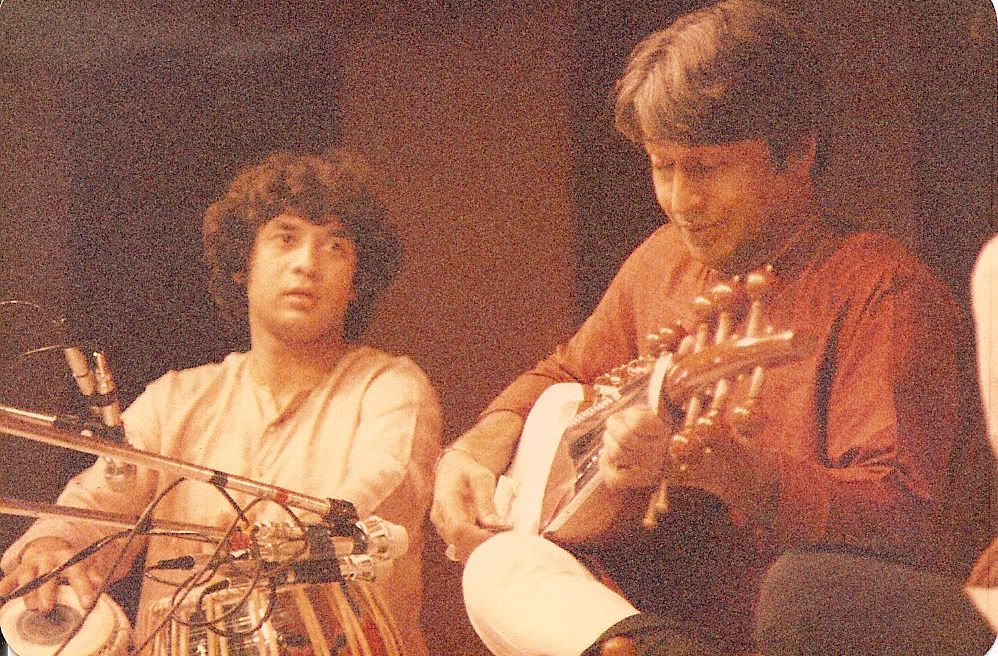

Amjad Ali Khan and Zakir Hussain. Sawai Gandharva Mahotsaav, Pune, 1985

India Indian music music: genius Jaipur Gharana Kesarbai Kerkar khyal

by Warren

10 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Kesarbai Kerkar’s Music Is, In Fact, Out Of This World.

One of the greatest voices of the twentieth century belonged to Kesarbai Kerkar, the legendary singer of Jaipur-Atrauli tradition, who bestrode the narrow concert platforms of India like a colossus until a few years before her death in 1977. To listen to Kesarbai is to experience intellectual, emotional and artistic depth in a way that can hardly be matched anywhere else.

Nat Kamod

India Indian music music photoblogging: Dagar brothers dhrupad

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

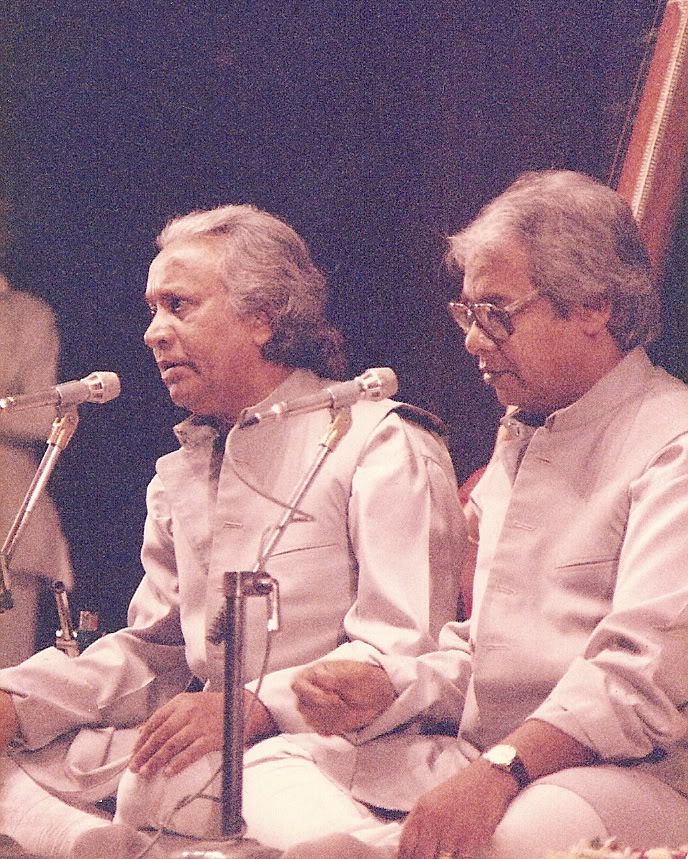

Dagar Photoblogging: Pune, 1985

These photographs were taken at a Dhrupad Sammelan in Pune, late in 1985. These are Zahiruddin and Faiyazuddin Dagar, the “Younger Dagar Brothers.”

Zahiruddin (L) and Faiyazuddin Dagar.

Education India Indian music music: drone gesture R. Murray Schafer silence Singing Imagination tamboura texture

by Warren

3 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Some Thoughts on the Drone

The drone lives at the center of Hindustani music, and yet I think its significance has rarely been stated completely. To say that it affirms or creates the tonality is to state the obvious; rather, think of the number of musical systems in the world in which the drone is implicit or only occasionally stated. Why then is the tamboura so essential in Hindustani music? In concerts, a singer often gestures to the tamboura players, indicating “more force, more volume!” — why?

R. Murray Schafer, that marvelously creative Canadian composer and educator, offers us a complementary pair of terms, gesture and texture. Hindustani melody is gesture refined and elaborated; gesture with fractal sub-gestures endlessly revealing themselves to careful listening. The complement to a gesture is a texture, where elements are sustained with enough consistency that they form a ground, a backdrop — a context within which isolated ideas can be heard and appreciated.

Education Indian music music: practice riyaaz

by Warren

4 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

More Notes on Practicing

More material taken from my long-ago interview with my student Brian O’Neill. This discusses a practice technique called:

One Lick for Two Hours

Now, when you’re trying to build up speed and technical fluency the following exercise is very useful:

Compose a line (preferably in your head) 2 or 3 notes at a time… and keep building it up until you have something that covers the range that you want to cover and includes whatever kind of technical things you want to address (scalar segments, intervallic jumps, whatever).

Switch the metronome on (at around 60 bpm) and do the line in half notes, keeping the metronome not on the downbeats, but on the upbeats (2 & 4). That is, your sung articulations and the metronome’s strokes aren’t happening at the same time.

Go through the whole line in sargam, in neutral syllables, and in open vowels. If you’re an instrumentalist, go through the line using individual articulations on each note, then with a legato approach.

At which point you double the speed, so that the same line is now sung in quarter-notes, one note per pulse. The metronome needs to stay on the offbeats! Again, do it in sargam, neutral syllables and one or two open vowels.

Then go back to the original tempo and revisit that for a few iterations.

Now move the metronome up a click. If you have a digital metronome, go up by three or four beats per minute.

Repeat the process exactly as before, and when you’re done, move the metronome up another few bpm.

Eventually you’ll get up to mm 120, which is exactly double your starting tempo. Do the same exercise at that tempo…and then shift the metronome back to 60.

Only this time, maintain the same sung/played speed you had at mm 120 — with the metronome at the slower tempo. Now you’ll be singing the line in quarter and eighth notes relative to the speed of the metronome.

Repeat the alternation of “single” and “double” speed, with the metronome still on 2 and 4. (For extra credit, why does this practice work better when the metronome’s on the offbeats?). Keep going up by a few bpm at a time.

Eventually you’ll reach a point where you can go no further; a point where your technique is on the edge of failure.

Don’t stop the practice just yet. Instead, back down by a notch or two, repeat the material, then back down again. Do this eight or nine times, so that when you finally conclude the practice, you’re midway between your maximum speed and mm 60.

Stop.

Go take a walk or something. That’s enough of that practice for the day.

This is not a ten minute practice, this is a two hour practice. Two hours on one lick. The important thing is to keep that process going, all the way up and then retreat, incrementally, back down to about halfway from your original starting point.

This gradual up and down incrementation turns out to be very useful for building a solid technique at all levels of speed. It’s boring as hell, but it works a treat.

I remember sitting down to practice in my apartment in Pune. I was practicing Yaman, I sat down to practice, and I practiced one line for about an hour and forty-five minutes — using this metronome technique. Then I finished, I turned off the sruti box, and immediately my doorbell rang. And I went over and it was Atul, the sitarist in my ensemble. And he said, “That was incredible!” I said, “You were listening to the practice? How long were you there?” He said, laughing, “Oh, I arrived just before you began!” So he had been outside my door for an hour and forty five minutes listening to me go over the same thing and he was completely thrilled to have heard this practice. That was very interesting to me. Not everybody would find that interesting, but Atul did.

Pt. Dinkar Kaikini, R.I.P.

I just learned that Kaikini died earlier this week in Mumbai. I have always been extremely fond of his singing. Here are two clips for your enjoyment. First, a wretchedly bad video with a sublime rendition of Todi:

and second, this beautiful Kabir bhajan:

Many years ago, when I was in Pune under Bhimsenji’s auspices, Pt. Kaikini was visiting the Joshi residence. I was practicing in an adjacent room. After he left, Bhimsen’s wife Vatsala came into the room where I was singing. She said, “Pandit Dinkar Kaikini heard you singing, and he said ‘This one will be a singer.’ ”

In those days I didn’t get a lot of encouragement, so those words fell very sweetly on my ears. I’d loved Kaikiniji’s singing already, but his kindness in making that comment was really the icing on the cake.

Many of his commercial cassettes are excellent. While his voice is not for everyone, I love it.

Goodbye, “Dinarang.” Rest in Peace.

Education Indian music music: paltas patterns permutations practice Raga riyaaz

by Warren

9 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Thinking About Palta Exercises

More of the material from my long-ago interview with my student Brian O’Neill. Here, I discuss the permutational practice routines known as Palta Exercises.

Hindustani musicians already know what I’m talking about. Western musicians will describe them as short phrases transposed up and down a scale: 123, 234, 345, 456, etc.

Paltas can be practiced within ragas, of course, but they are also useful for practicing ear-training and pattern manipulation inside scales.

To clarify the distinction: a palta in Raga Bhimpalasi would accommodate the omission of the second and sixth degrees in ascent, and the inclusion of these notes on the way down. Violating the raga’s rules of motion is off the table. On the other hand, a palta in Kafi Thaat (the Dorian mode, if you will) would not have any such restrictions.

Here’s a useful way to do paltas:

Pick a scale — any scale, preferably one that has 7 notes. Take a single short pattern (let’s call it a “cell”), and transpose it up and down in the scale.

For example:

S N S / R S R / G R G / M G M / P M P / D P D / N D N / S N S

N D N / D P D / P M P / M G M / G R G / R S R / S N SAnd once you’ve memorized it, then do another pattern.

S N D / R S N / G R S / M G R / P M G / D P M / N D P / S N D

S R G / N S R / D N S / P D N / M P D / G M P / R G M / S R G…Again, do that for 10 minutes.

And then alternate the two patterns, one after the other. Do it all from memory.

Then combine the two patterns:

S N S / S N D

R S R / R S N

G R G / G R S

M G M /M G R

P M P / P M G

etc., over as much of a range as you feel comfortable singing or playing.Then try combining the two in the other order:

S N D / S N S

R S N / R S R

G R S / G R G

M G R / M G M

P M G / P M P

etc.Try doing two iterations of the first “cell” and one of the second:

S N S / S N S / S N D

R S R / R S R / R S N

G R G / G R G / G R S

etc.Begin making up your own combinations of cell sequences, always using your memory to keep the material fresh in your mind’s ear.

Try, instead of alternating cells, alternating successive notes of the two different cells. S N S / S N D thus becomes S S N N S D; S N D / S N S becomes S S N N D S.

Instrumentalists should be singing these patterns as well as playing them. It is also a very good exercise to sing while fingering them on your instrument (without activating it in any other way). This builds a powerful cognitive link between instrument and voice that pays off in future fluency and expressiveness.