Education music Personal: Bamidele Ousamarea instrument-making Lou Harrison

by Warren

5 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Summoning The Future — Making Your Own Instruments

Making an instrument is one of music’s greatest joys. Indeed, to make an instrument is in some strong sense to summon the future. …. Almost no pleasure is to be compared with the first tones, tests and perfections of an instrument one has just made. Nor are all instruments invented and over with, so to speak. The world is rich with models — but innumerable forms, tones and powers await their summons from the mind and hand. Make an instrument — you will learn more in this way than you can imagine.

Lou Harrison’s Music Primer (quoted in Banek & Scoville, “Sound Designs”).

I remember reading somewhere that a natural ecosystem that had taken thousands of years to develop can be destroyed in ten minutes by a guy driving a bulldozer. That seems true enough; horrifying and depressing, but true. All evolution’s gradual work, building a wonderfully complex interdependent structure — turned into undifferentiated rubble in less time than it takes to read a blog post (yeah, I know, mine run on the long side, but anyway).

Think about ecosystems as analogies for the ways human beings relate to one another. Traditional societies are rich in ritual frameworks, cross-generational relationships, nuanced interactions with the natural world and shared cultural narratives — another “wonderfully complex interdependent structure” that can be trashed appallingly quickly by the bulldozer of Western consumer culture.

Singing enabled individuals to create and express certain aspects of self, it established and sustained a feeling of euphoria characteristic of ceremonies, and it related the present to the powerful and transformative past. The Suya would sing because through song they could both re-establish the good and beautiful in the world and also relate themselves to it.

Anthony Seeger — “Why Suya Sing,” p. 128

If we are to reclaim our humanity, we’ll need to sing. We’ll need to make music ourselves rather than buying it from someone else.

And one of the most meaningful ways to get started with that process is to make an instrument. Or two. Or three.

———————————————-

A mini-washtub bass

The first instrument I remember making was in 1970 or thereabouts. I’d seen a jug band perform and was deeply impressed with the washtub bass (I have always had a thing for low frequencies). I went home and over the next few days….

Located a big square tin can (maybe 12″ high by 10″ square) that used to hold some sort of pourable liquid, rinsed it out, and fitted a five-foot piece of pine corner molding through the hole where the cap went and down to the bottom of the can. I fixed the molding at the bottom by pounding a nail through the tin and into the end of the molding. I poked a big nail through the top of the can at the opposite corner, making a new, smaller hole — and threaded a piece of clothesline through it. I swung the assembly around until I could grab the end of the clothesline through the pour hole and tie a big knot in it.

I then pulled the clothesline tight and fastened the other end to the top of the piece of molding, which was flexible enough to bend but not break. Presto! A portable mini-washtub bass (with a carrying handle, no less)! I subsequently took another nail and made a rosette pattern of holes on the side of the can as a “sound hole.”

My first instrument. I wonder what happened to it. I carried it around a lot, and played it (mostly by myself — I didn’t have any friends who wanted to be in a jug band, alas).

———————————————-

Fast forward about ten years. I’m a college student (in a design-your-own-major / alternative-higher-education model), looking for someone to teach me how to make drums. My college can connect me with harpsichord-makers, but what I really want to do is to learn how to make djembes. I’d acquired one from a local pawnshop the previous year. Beautifully decorated and inlaid, carved from a single hardwood log, this exquisite hand drum was an absolute steal at $40, and I loved to play it. And I really really really wanted to learn to make one.

I was hitch-hiking home from a singing lesson when the battered green Subaru pulled up. Inside it smelled excellent. At the wheel was a short, bearded Afro-American man with a great mass of dreadlocks. I hopped in. There was something excellent smoldering in the ashtray.

We chatted. His name was Dele (pronounced like “delay,” and short for “Bamidele”), and he was the musical director of an African dance company. “I make drums,” he said.

“Really?”

“Yeah. Wanna see? Look in the big blue duffel bag in the back.”

I opened the bag, and my eyes opened wide. “Oh, wow! I have a drum at home that’s just like this! It’s got red and blue squares alternating around the bottom…”

He finished the sentence: “…and black vertical lines? And it’s painted white on the inside?”

“Yeah!”

“That’s my drum! It was stolen from me!”

“I bought it at a pawn shop last December!”

“Oh, man, I’ve gotta get that drum back.”

“Well, I’ll gladly give it back to you if you’ll teach me how to make one.”

“Hell, yeah!”

And he fired up another joint and we drove to my apartment, where he picked up his lost child, crooned over it briefly, gave me a loaner drum to play, and made a date to get together.

And that was the start of my instrument-building apprenticeship. Once or twice a week I’d ride the subway to Roxbury early in the morning and walk to Dele’s house. The first day was unforgettable. I arrived at about 9 am. He was already outside, carving a circular cavity in the middle of a tree stump. Freehand, with a chainsaw. With a big spliff hanging out of his mouth.

He saw me coming up the driveway. “Yeah, Warren!” he shouted. “Get in the car and we’ll go find some junk to make instruments with!”

And I did, and we did, and we did.

That day, we made a bass kalimba.

———————————————-

A bass kalimba

Here’s how it went:

Step 1: locate a discarded chest of drawers. Hop out of car with crowbars; reduce to pieces that will fit in car. If the bottoms of the drawers are made of thin plywood, that’s excellent!

Step 2: locate a construction site. Within a few yards you’ll find some of the metal strapping tape that is used to bind together lumber.

Step 3: find some pieces of smaller flat wood (1/2″ square or so), any length greater than 4-5 inches.

Step 4: bolts, nuts, washers, nails, glue.

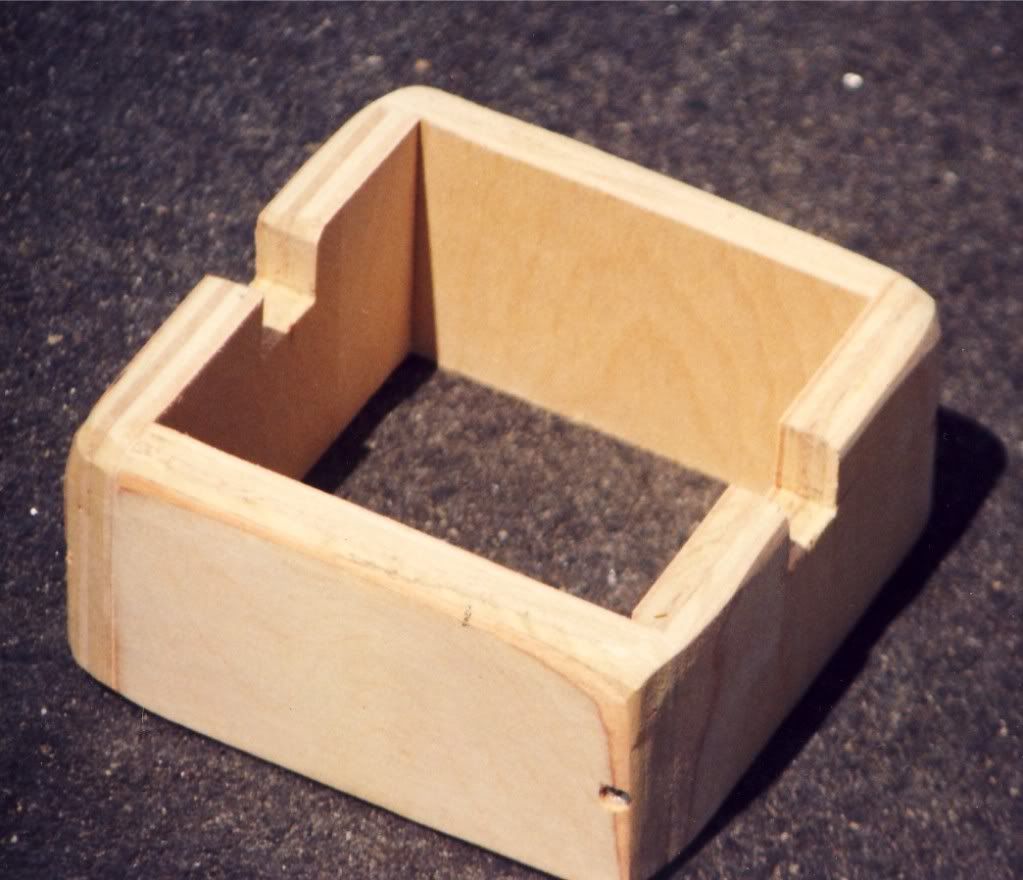

Make a box. If the dresser you cannibalized has intact drawers, don’t bother taking them apart; just use them as is (a drawer is a box).

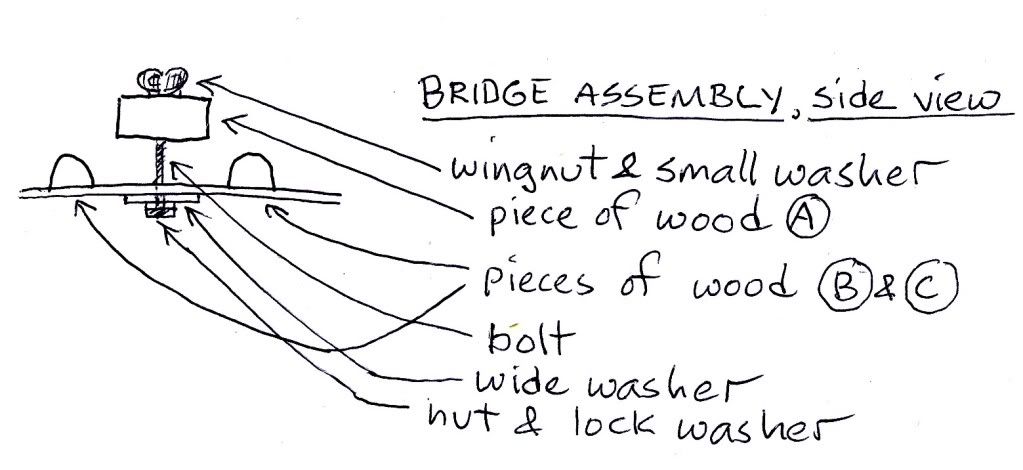

You’ll need a piece of thin plywood that will cover the entire top of the box. The back of a trashed bureau should do nicely. To this you will need to attach the bridge assembly. You can drill all the necessary holes and insert the necessary bolts before attaching the top to the rest of the box. Cut a hole in the top that’s big enough to put your hand through…but not much bigger. Here’s a side view of the bridge assembly:

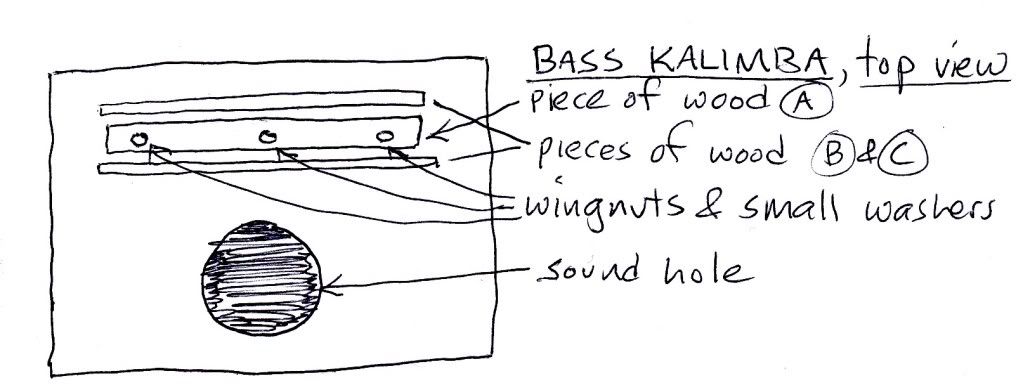

Now attach the top board to the box. Use nails and glue, and make sure it seals properly all around. Pieces of wood B and C can be glued to the top. It should look like this:

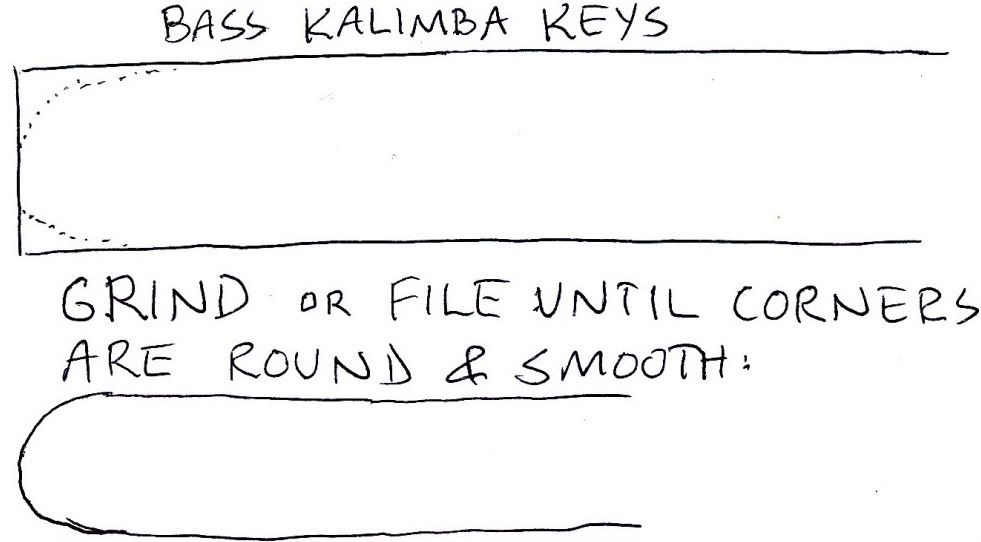

Snip the metal strapping tape into short lengths ranging from 4 to 6 inches:

These are the bass kalimba’s keys. Fit them under A and over B & C, then tighten the wingnuts (and how long has it been since a political blog featured the original meaning of the word “wingnut”?) until A presses down on the keys and they bend upward. Wiggle the keys back and forth to lengthen and shorten them. The shorter they are, the higher their pitch; the longer, the lower.

———————————————-

Dele and I kept up our work together for over a year. His immediate response to anything he saw was to imagine it as part of an instrument. Eventually I made a djembe — we found a big pine log and under his supervision I carved out the middle into the drum’s form, before shaping the outside. It sounded beautiful and I played it for years. When we made the instrument, he told me “pine will last ten years; hardwood will last a hundred years.” Eventually the pine split slightly, right on schedule. I still have the drum body in my basement. One day I’ll patch it up and play it again.

Dele died sometime in the late 1980s or early 90s. I wish I could call him up and thank him for what he taught me. Lou Harrison: “To make an instrument is in some strong sense to summon the future.” Every time I make an instrument I summon the future, and I am linked to my past, to the man who taught me how to think as an instrument-maker. When I teach students to make their own instruments I remember Dele very strongly. I am nowhere near the artist he was, and I am grateful for having known him and learned from him.

———————————————-

I remember visiting the dump with my father; almost invariably we’d return with more than we’d brought. Old radios which he swore he’d fix up (but never did), lengths of board, metal shelving — once, he brought back a giant movie screen that must have been in a school auditorium or something…it was about 25 feet long. People always threw stuff out, and it was always reusable, salvageable, or functional.

Not quite as much, nowadays.

One of the things I regret most about our cheap disposable society’s addiction to cheap disposable junk is that the stuff people throw out can’t be used for anything else. Most of the furniture that shows up on trash day nowadays, for example, is wretched particleboard crap.

Wood has grain, which is directional. This gives the wood springiness and flexibility (good for resonance), but when it’s sliced really thin, it’s pretty easy to break. Plywood is made of alternating layers of thin wood, each layer with grain 90 degrees to its neighbors. This increases strength but decreases resonance.

Fortunately, thin plywood works well enough for my purposes; it’s strong enough and flexible enough that I get resonance, and my instruments aren’t so delicate they need protection, for example, from rooms full of fourth-graders.

But particleboard? Particleboard is wood chips and sawdust mixed with resin and molded into boards. No grain. No springiness, no resonance. Particleboard is absolutely teh suck, and I sometimes see it as a compelling demonstration of how our distorted consumer culture pulls the value out of things.

It started out as a way of utilizing sawmill leftovers, but manufacturers discovered that the more uniform the particles, the better the product. Which meant, of course, that trees were simply cut down and fed into chippers. That’s a lot cheaper than slicing long thin sheets off a rotating log and then gluing them back together to make plywood. Which is why you can get all that great stuff from IKEA for so little.

Do us all a favor: if you buy particleboard furniture, buy better-grade stuff, and take good care of it. Find a home for it if you no longer want it. Don’t just throw it out, because it’ll be useless.

Our industrial history has shown that the way to make money fast is to ensure that a thing can only be used once before it must be thrown away. For the most part, you can’t salvage particleboard. If you try to cut it, you’ll generate massive amounts of toxic dust (formaldehyde, anyone?), and it’s not very good for your sawblades either. You can compost wood chips, but you can’t compost particleboard; it’s got all sorts of terrible chemicals that you don’t want in your garden. That cheap bookshelf goes straight from K-Mart to the landfill, with a 2-year interval of outgassing in your apartment.

This is the result of manufacturing at the intersection of overpopulation and industrial-monopolistic capitalism. There are too many people, all of them needing stuff now — and there’s no time or resources to make things individually, and not enough money to pay for the artisans’ time.

Which is why it’s practically a moral obligation to salvage that old dresser being thrown out down the street on Trash Day. Those drawers have real half-blind dovetail joints; even if they’re machine-cut, there’s time and ingenuity and human labor embedded in every square inch of that piece of furniture.

But I digress.

———————————————-

Drums

Everybody should know how to make a box. When I do instrument-building workshops for adults, I am invariably amazed and horrified at the number of people who think this is some kind of incredibly arcane process. It’s not. People have been making boxes for a long time.

If you make a box, but you don’t cover the top or bottom, you have a box frame. You can do a lot with a box frame.

Making a box frame drum.

Soak some rawhide goatskin in water. Round off the corners of one side of your box frame.

Glue and staple the skin across the rounded side of the frame. Use lots of glue (Elmer’s is fine) and lots of staples. Try to be neat. Wipe off the excess glue from the underside of the skin, and let it dry for twenty-four hours.

Attaching the skin.

You’ve made a square drum. If you can find real heavy-duty cardboard tubing (with a wall thickness of 3/8″ or more) you can make a round drum.

Once you make a drum with rawhide, you are bound up with the goat that gave its life for your drum. Failure to play the drum is a failure to acknowledge that a living creature died for your music. So play the drum, and honor the goat!

———————————————-

When I was living in India, I decided to buy a batch of goatskins to take home with me for instruments. Because of the caste status of people who deal in dead animal stuff, the drum-maker’s place was located smack-dab in the middle of the whores’ quarters. Rickshaw drivers would give me very knowing looks when I gave them the destination. And what could I say in my fractured Hindi? “No, actually, I’m just going down there to get some skin?”

Fortunately, you can purchase goatskins very easily and cheaply through online sources. Shorty Palmer is my source for goatskins.

———————————————-

Banjos

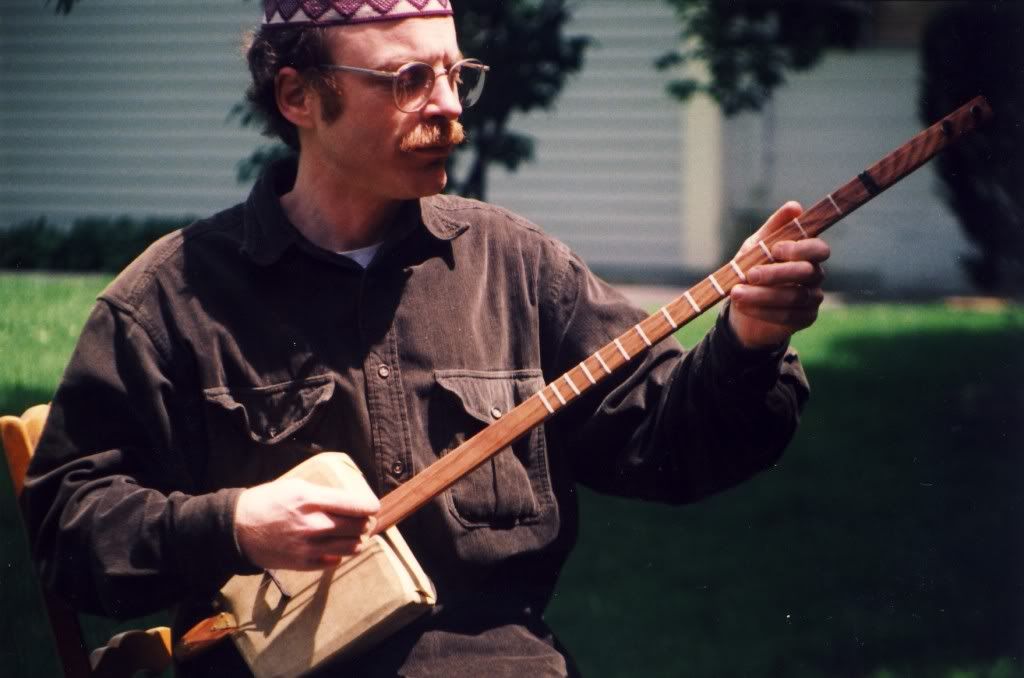

To make a banjo, you’ll need a piece of hardwood for the neck, and some scraps of plywood or any boards for the body. And some goatskin.

Make a box, and cut two notches that match the width and depth of the piece you’re using for the neck:

Make sure the neck piece fits snugly. Before you attach it to the box, you’ll need to refine it a bit.

Use a file, a saw or a rasp to remove some wood in the part of the neck that will be inside the box. You will be putting skin over the top eventually, and there needs to be some space between the neck-piece and the skin. While you’re at it, round off the sides of the neck-piece where you’ll be holding it while playing, and sand them smooth. Drill some holes at the far end of the neck for tuning pegs. There is a tool called a reamer, which makes tapered holes. It’s a good thing to have in in your toolbox. You can whittle a piece of wood into a roughly tapered peg; put a piece of sandpaper in the tapered hole you’ve made with your reamer, and it’ll shape itself nicely. Remember, people have been doing stuff like this for thousands of years. Add an extra little piece of wood just ahead of the tuning pegs; the strings will go over this (it’s called the nut, by the way).

Glue and screw the neck into place, and attach the skin just as if you were making a drum. Let it dry for 24 hours.

I had a little scrap of ebony lying around that I used for a bridge, but really any small piece of wood will do just fine. Many of the stringed instruments I make are fretless; this one has tied frets made of waxed thread. Sometimes I make tied frets from a readily available organic string which grows wild in Montana.

For strings, I used monofilament nylon fishing line. It sounded great.

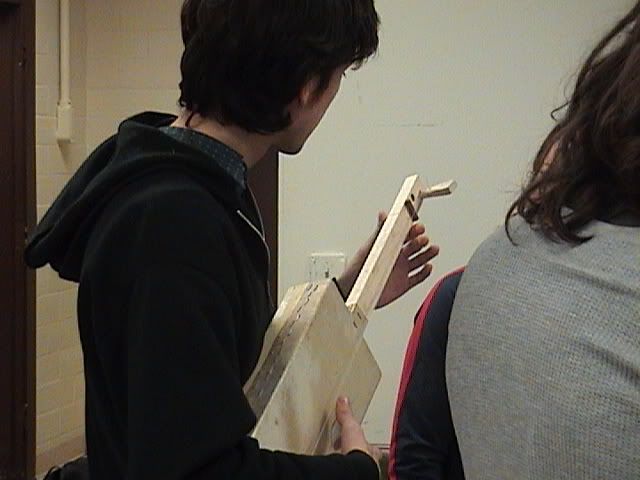

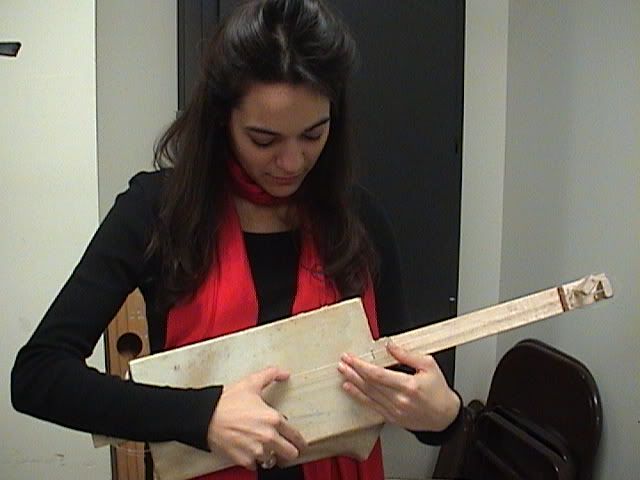

Here are some of my students with banjos they’ve made:

———————————————-

Now understand me: the goal of all this is not to be a great virtuoso, or to sell your instruments to the world, or to attract the applause of your audience. The goal of all this is to do it yourself. Because once you make an instrument yourself, as Lou Harrison said, you’ll learn more than you ever imagined possible. If you do it with a child, what do you think they’ll learn as they watch? Once you start doing this, the world will be full of musical resources for you.

I don’t give a damn if you think you’re “tone-deaf” or “unmusical.” Nine-hundred-ninety-nine thousand, nine-hundred-and-ninety-nine times out of a million, that’s not true. Our culture has commodified music, turning it into a consumer good that’s produced by a specialized, isolated occupational subcategory. In cultures where that hasn’t happened, everybody sings and plays music. And where everybody sings and plays music, people (even people with few or no possessions) are happier; their communities are more robust; they treat one another better. The loss of communal musicking in our civilization is a profound tragedy, one of the greatest losses in the wake of the cultural bulldozer.

And there’s another reason. America is number one in the world when it comes to making trash, which is another way of saying subtracting value from stuff. We USA folks are more effective than any other culture in the world at making things valueless. Making musical instruments from things other people throw away is a way of adding value to stuff.

———————————————-

Xylophones

Get a piece of scrap board and attach two short lengths of scrap 2×4 to it, one parallel to the edge, one at a slight angle, so that the space between the 2x4s gradually narrows. This is the frame of your xylophone. Find some narrow scrap wood and cut a set of graduated lengths. These are your keys. The keys need to be 166% longer than the spaces between the 2x4s (if the space narrows from 15 inches to 9 inches, your keys will need to range from 25 inches to 15 inches). If your measurements are a little off, no problem.

Line the keys up on the 2x4s, and mark their locations. Drill some 1/2′ diameter holes between the key positions on one side, and in the middle of the key positions on the other side. Cut some 1/2″ dowels to about 4″ long and glue them in the holes.

Drill 5/8″ holes in one end of each key, about 1/5 of the way in from the end.

Using rubber bands, old foam rubber, or pieces of sponge, create a bouncy surface at the top of the 2x4s.

Put the keys on; the 5/8″ hole goes over the dowel that’s in “mid-key” position.

Xylophone keys are easy to tune. Using a file, remove wood a little bit at a time from the middle of the key, on the underside. This will make the note flatter. Try not to overshoot your destination tone, because making the keys sharper is much more time consuming (remove wood from the ends instead). Tune it so it sounds good to your ear. Take some rubber bands and wrap them around some sticks to make mallets, or use a long length of glue-soaked string for a harder surface.

———————————————-

R_____________, a violist at New England Conservatory, came up to me after class a few years ago. She said, “I need to tell you something. Last week I made a three-stringed zither in class, and I took it home.”

I remembered. The instrument had twin tin cans for resonators.

She continued, “I haven’t practiced all week. Every day I come home and instead of practicing viola, I sit on the couch and play my zither. Just the same three strings over and over in different combinations. It’s totally fascinating.”

I said, “How’s your viola playing?”

She replied, “That’s the weird part. It’s gotten a lot better.”

———————————————-

Some real simple instruments:

I found a discarded wicker laundry basket in the trash a few years ago. I took it to my shop and carefully disassembled it, saving the wicker pieces in a cardboard box. In a workshop the following year, my students cut the pieces into uniform lengths, bundled them together and bound one end with rubber bands, making a sort of brush:

When tapped or shaken, they made a fine rattly-brushy percussive sound. Here’s what seven of them (along with a bass kalimba and a recycled-water-bottle maraca) sound like (added one at a time in this rhythm game):

Save plastic water or juice bottles. Rinse them and let them dry. Put in a handful of rice or beans. Different amounts of different materials give different sounds; a garbonzo rattle sounds nothing like a rice rattle. If you want to get fancier, a cut-off piece of broomstick can be made to fit in the neck of the bottle (epoxy is sometimes necessary, but often a friction fit is fine). Kids enjoy decorating these rattles.

Different sizes of tin cans give different sounds, and you can make quite an effective “steel band” by putting together an ensemble of people playing different parts on their various cans.

Any kind of tubes (cardboard, plastic, metal) are a fabulous source of music. I often use the plastic tubes that protect flourescent lightbulbs in many industrial situations. Cardboard tubes from shipping contexts are excellent, but you can’t hit them together or they’ll break. Glue a little piece of plywood across one end, and the closed tube will make a very satisfying pitched sound when you tunk it on the floor. Varying lengths yield different pitches, the longer the lower. You can distribute them to your friends at your next party and have a fabulous jam session…or you can practice as a soloist and hope to rival this guy:

———————————————-

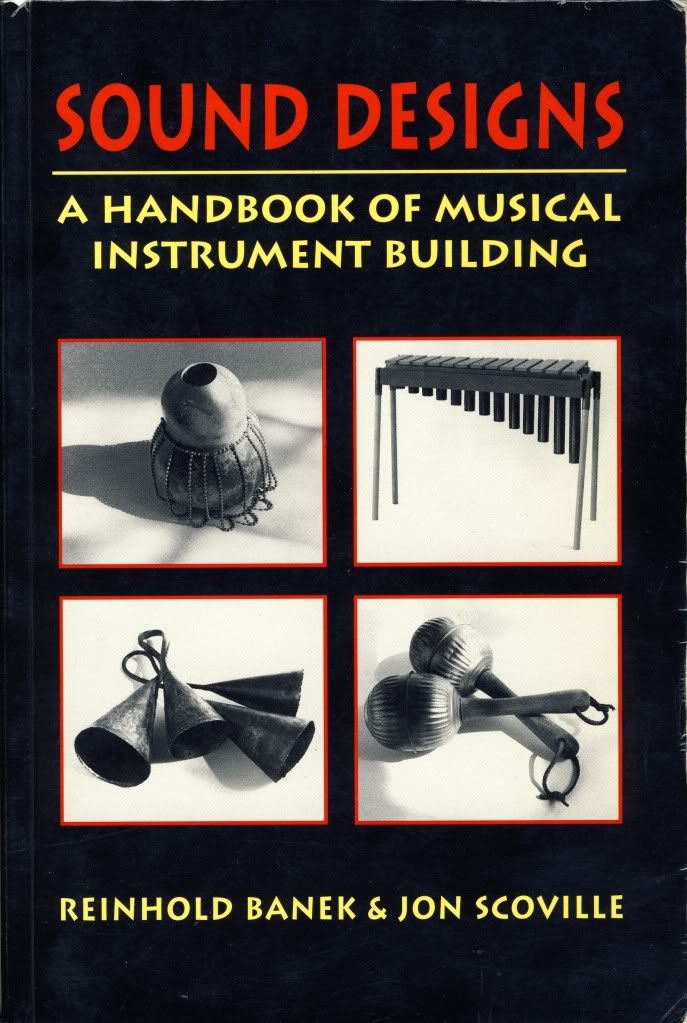

The single best resource for would-be instrument-makers is this book:

———————————————-

I am not sanguine about the short-term future of our species. The signs of a climatic catastrophe are unmistakable to anyone who’s paying attention.

My hope is that we will come through this and know something more once the world’s environment stabilizes in a thousand years or so. I don’t know if what I’m doing is really that helpful…but it’s what I know how to do.

One thing I know is that if humanity doesn’t nourish and nurture the rapidly disappearing skills of group singing and group musicking, we will be a lot less likely to survive. So…for our planet’s sake, and for your own — sing and play with people! And make some instruments from whatever you’ve got lying around. There is no more human thing to do in this world.

But yield who will to their separation,

My object in living is to unite

My avocation and my vocation,

As my two eyes make one in sight.Only when love and need are one,

And the work is play, for mortal stakes,

Is the deed ever truly done,

For Heaven, and the future’s sakes.— Robert Frost, “Two Tramps in Mud-Time”—

Thanks for reading.

Aloha from Hawaii. Oh yes!! Mahalo nui (thanks!)for this rich post . . . I want to create the capability for teens to sing and create together, & this post is fabulous for inspiring teens to create musical instruments . . . which they will then play together and perform for others . . . all the while creating the future they want! Love to you!

absolutely great article!thank you for some great inspiration this morning. I’m a luthier, have built renaissance string instruments, sitars and ouds, lots of other stuff.I hev great and humble respect for the builders of exquisite and refined instruments but also cheer for anybody making things with their hands.

I just saw Bassekou Kouyate and Nkoni Ba- master players of the Bamana nkoni. that’s probably THE oldest lute specie, identical to ancient Egyptian ones, and a very simple instrument. but the total sorcery of their technique was mind blowing and the concert they did was one of the best I’ve seen in years.a very good lesson here for musicians and builders: something that simple can go way beyond anything you could imagine, it’s all in the skill and technique of the player. take a look at bansuri flutes from India- a piece of bamboo with holes burnt in it( but very painstakingly determined actually)and then listen to one of the Indian masters play it.

I pray everyday for the preservation of the non-western world’s traditions.if we listen and learn from them, it might save the whole world.

“Think about ecosystems as analogies for the ways human beings relate to one another. Traditional societies are rich in ritual frameworks, cross-generational relationships, nuanced interactions with the natural world and shared cultural narratives — another “wonderfully complex interdependent structure” that can be trashed appallingly quickly by the bulldozer of Western consumer culture.”

Thank-you, Warren,

Indeed, I am of the belief that it may be worthwhile to think very much about living cultures as inter-dependent ecosystems; why something must be done to preserve them, and how unchecked “modernization” will impact future generations in every manner including the sustainability of a viable artistic and intellectual environment – or as you so well put it, “ritual frameworks, cross-generational relationships, nuanced interactions with the natural world and shared cultural narratives”

Speaking for myself, I find the loss of so many venerable, long-lived cultures just as devastating or more so as the loss of ancient forests and animal species.

My cousin recommended this blog and she was totally right keep up the fantastic work!

If you do anything in this line, let me know. If you have pictures I’ll gladly show them here.