atheism: personal recollections

by Warren

6 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Growing Up Atheist

I am a member of the most feared, hated and despised religious minority in the United States. I am an atheist. For years I never talked about it…because I’ve always been an atheist; I never thought there was anything particularly noteworthy about it.

But a few days ago I got into a conversation with an old friend who was in favor of tax-funded prayer in the public schools, and I “came out” as an atheist to him. The subsequent back-and-forth was long and deeply unsatisfying, and reminded me anew of the amazing array of our society’s misconceptions and fears about what atheists believe, about who we are, about what we’re like.

Well…

I grew up in a family of atheists, and most of the people I’ve been close to over the course of my life have been atheists, agnostics, secular humanists and Hindus. This article was originally written for the “Atheist Digest” series at Daily Kos, and I wanted to write it because one of the questions that is always asked about atheism is, more or less, “What shall we tell the children? How do we teach them ethics and morality without God?”

I was one of those children.

In which I discuss being a child in a family of atheists.

I have never prayed.

I didn’t pray when I was growing up. I went to church when we visited my mother’s parents, typically once or twice a year. I never spoke the prayers out loud, and never sang the hymns. In school, I left out the phrase “under god” from the Pledge of Allegiance, and in Boy Scouts I omitted “God” from the “God and my Country” phrase from the Scout oath (I confess I didn’t last long in the Scouts anyway, although it was a longer tenure than that of my brother, who got tossed out for giving the scout salute with the outer two fingers omitted).

My mother’s parents gave my brother and me Bibles one Christmas. I was then (and have always remained) a voracious reader, so I read the Bible, cover to cover. Most of it was incomprehensible, but I trudged on, because that was what you did with books: read them from cover to cover. Later on, in my teens, I found some lovely poetry in Ecclesiastes, and there’s a blue denim jacket in my closet with a verse from that chapter incorporated into a lot of hippie embroidery on the back.

The quote reads, “Better is a handful of quietness than two hands full of toil and a striving after wind.” One of these days I’ll start teaching my daughter to embroider.

But from the point that I understood myself to be anything in the frothing confusion of religious identity, I understood myself to be an atheist. My parents were atheists, and when I asked them questions about important things, their answers made sense. I never felt a need to rebel against a deity or a religious tradition, because there was nothing for me to rebel against. I didn’t rebel against atheism, either, because my parents never forced it on me. They just worked and played and did the best they could bringing up two boys in a suburb of Boston while the cultural storms of the 1960s swirled around us.

The house was full of books, and full of discussion. Most of my school friends found our family dinners to be unnerving; conversation was incessant and filled with philological digressions. Often I was the designated looker-upper; when a point of argument hinged on the correct meaning of a word, I would have to get up and go to the nearest dictionary and provide the main and supplementary definitions along with etymology and any interesting tidbits of usage — following which, dinner would continue. My parent’s friends were scientists; we did not to my recollection know any people who were overtly religious.

I encountered religion peripherally. The Pledge of Allegiance is one such instance. The lyrics to songs like “America the Beautiful” are another. At some point I must have asked my parents what this stuff was that I kept hearing, about “God.” My mother recalls:

We were sitting in the living room, and having a discussion about religion…and [I told you about] how, long ago, when people didn’t have as much scientific knowledge as we did, and they needed answers to big questions, they made up gods. Gods were their answers, and it was unscientific because…they didn’t have science, and these were their answers. And you took that very seriously.

My father had this to say when I asked him recently for his view of religion:

…religion in my view is a particular variety of self-deception, and I think it stems from a primitive by-product of the central nervous system which makes people want to know why. Given primitive ignorance of anything other than “if you hit a dog with a club you can knock him over, if you drop a stone, it falls…” from the point of view of what the nature of the world is, all these phenomena have to have causes…“why does the stone fall, why does the sun shine?”

…If you don’t know, the need for rationale requires that you invent a cause, and my feeling has always been…that the modern religions are really the manifestation and crystallization of cumulated irrelevant explanations, coupled with deep brutality toward people who have different explanations. In other words, people fell in love with their own unfounded explanatory statements, and therefore had to fall out of love with anyone who suggested something different…and I think it’s still going on. With that, we have religious wars in which people do everything that violates all the tenets of their religion. The Catholics at one time had the inquisition, and the extension of Islam by the sword is reasonably well documented…but all of these were to defend the causal charade, because it was more troubling for people to be told that their explanation is wrong than to be put in the position where they had to cut the heads off of other people.

Both my parents were psychologists, in consequence of which my brother and I yearly accompanied my parents to whatever city was hosting the annual convention of the American Psychological Association. While most of the talks and presentations were over our heads, I remember vividly a film on some aspect of the commune movement (this was during the sixties, remember!) that ended with a few seconds of the commune’s members, arms linked, singing a long-drawn-out OM. The sound mesmerized me; it lodged itself in my imagination where it remains to this day. Indeed, when I have optimistic thoughts about what will happen to me when I die, I find myself hoping that I can simply rejoin the Great Hum of the Universe.

In which I decide that I am a pacifist.

My mother’s brother was also an atheist. Once I asked why, if he was an atheist, he had a small Buddha on the dashboard of his car. My mother said it was because when he lived in India, he was aggravated and angered by the superstitions he encountered, and the statue was to remind him of this. That doesn’t make a lot of sense, but it’s what I remember.

I don’t know how I encountered the notion of pacifism, but by the fifth grade I had decided that I was a pacifist and would not fight. I jokingly announced that I was a Buddhist, but this was a joke; I knew nothing of Buddhism beyond the fact that Buddha was a pacifist.

What I do remember about becoming a pacifist, however, was that it seemed to make people angry. Kids would beat me up… for the reason that I would not fight them. And the teachers who were in charge of recess would say things like, “well, Warren, you should stand up for yourself.” Even at that age, I recognized this as a senseless response; I was standing up for myself — those playground bullies weren’t going to make me fight (bigbangit!).

Now, to be fair, I suppose a real pacifist would have acted to defuse the violence of the bullies; my grade-school agenda was more in the nature of deliberately provoking a violent reaction so that I could assert moral ascendancy over my peers. I may have been nonviolent, but I was also obnoxious.

Nevertheless.

I remember in seventh or eighth grade reading a line in one of Nat Hentoff’s young adult novels, in which a character quotes Cesar Chavez saying, “I am not a nonviolent man. I am a violent man who is trying to be nonviolent.” That impressed me deeply; I have many strong emotions that demand physical outlet, but the notion of violence against another human shocked me then and it shocks me still. Since fifth grade I have raised my hand to another person a total of twice; the memory of both occasions brings me sorrow and shame to this day.

In high school kids found out that I was a pacifist. I remember one big guy coming up to me and asking, “Hey, is it true that if I hit you, you won’t hit me back?” I replied, “Yes.” Whereupon he hit me. Hard. High school was a dreadful experience (it was for most of us, of course…but for a long-haired self-professed pacifist two years younger than anyone else in the class, high school was really and truly teh suck).

My mother discussed my pacifism with me, approvingly. This was in the mid-sixties, and I was too young for the draft, but she told me about “conscientious objector” status. I thought this was wonderful, for if ever there was a conscientious objector, it was I. But she told me that in the event that I ever became eligible for the draft I would probably have to be part of a church or religious organization, because their imprimatur was almost always essential for CO status to be granted. I did not know what to do; fortunately the war ended before I had to face this question.

In which I find a personal hero.

When I was in 8th grade my parents gave me Irving Stone’s wonderful book, “Clarence Darrow for the Defense.” I read it over and over, absorbing the details of Darrow’s life and legal career. One day my mother brought me home a slender paperback book: Lawrence and Lee’s great play, “Inherit The Wind.” I knew the story of the Scopes trial from Stone’s book, and the play enthralled me completely. One moment in particular struck me with great force: just after Henry Drummond (Darrow) calls Matthew Harrison Brady (William Jennings Bryan) to the stand, and Brady states his willingness “…to sit here and endure Mr. Drummond’s sneering and his disrespect.” In those days we didn’t have VCRs, much less DVDs, so it was another couple of years before I watched the film (when I was in high school) — but here’s the scene for your viewing pleasure. Brady asks “Is it possible that something is holy to the celebrated agnostic?” Drummond’s response never fails to touch something very deep in me.

In which I learn the power of group singing, and accidentally discover a spiritual practice.

I went to a wonderful summer camp for five years between 1967 and 1971; there was constant music at Killooleet, and it was there that I first experienced the power of group singing. I wasn’t a particularly good singer at the time, but the songs went deep inside me. For all that it’s become a synonym for mushy liberalism, I can tell you that sitting around the dying embers of a campfire and singing “Kumbaya” with a hundred other kids and grownups was a genuine communion, the effects of which still ring in me, forty years down the road. Killooleet was run by John Seeger, who’s now 95, and still active and vigorous (his younger brother Pete’s doing pretty well, too). UPDATE: John Seeger died peacefully in early 2010 in the presence of his family.

Once when I was at camp, all the kids in my cabin were on an overnight hike. We made our campsite by the side of a lake. During post-supper free time, I went and sat on the bank and looked out over the water. There was a buoy with a blinking light in the middle of the lake, and as I sat cross-legged I began to focus my attention on the light. I discovered that the combination of immobility and sustained attention to a repeated stimulus brought me to an unusual sort of mental stillness, which I liked. After a while, I went and got one of my friends, and said, “Jim…if you sit quietly and just watch the light, it makes your mind feel very different.” We sat there and watched the light together for fifteen or twenty minutes before it was time to go to bed. I had apparently discovered meditation.

In which I ask my parents about the origins of their atheism.

Before I go much further, let’s have a little bit of back-story. In preparation for this diary, I spoke with both my parents and asked them about their childhood experiences. Over the past fortnight, I’ve been enjoying transcribing the recordings, and I’ve learned quite a bit about my mom and dad, and about their lives.

My mother…

…was raised by two very religious parents who had different religions: a Catholic father and an Episcopal mother. I was raised Episcopalian, and at one time I thought I wanted to become a nun. I was very much interested in religion, and touched by it. Touched by the goodness of Jesus, and the fact that Jesus loved children and wouldn’t let anybody be brutal or rough with them.

…and then as I got to know, as I learned science…actually my real doubts started in junior high, when I wanted to be a physician, and that meant “be good at science.” I was active in church and believing in it, but it seemed to me — I thought a lot about what you might call existential questions, and one of them was determinism…and I didn’t see how you could be a determinist, which I became…and still pray. These two views of existence didn’t fit, and the further I went, the less I could accept. I didn’t understand the church doctrine….I learned words, tried to understand them, and got misapprehensions.

I was badgered about religion at home, particularly by my mother, a little bit by my father…

One summer I read H. G. Wells’ “Outline of History,” and there was a chapter in that on world religions. As I read it I was very much impressed with Buddhism. I thought, “This is really good,” and then I thought, “Why am I a Christian? Because my parents are Christians. But in the world, most people aren’t Christian; it’s just a…just a chance, a low-probability event that I happened to come into the world as the child of two Christians.” I kept that thought to myself, but I did comment that I had found what I’d read on Buddhism to be very interesting, and my mother was so shocked and horrified that I never mentioned it — I scarcely dared think of it again.

So I kept trying to understand, and…at the end of college, I wrote my parents a letter and said, “Now you’ve had a chance to bring me up and you brought me up Christian, and I would like to reject Christianity, and this will disturb you and sadden you, and I’m awfully sorry. It’s not a choice, it’s just the way I understand things, and I hope you’ll let up on me, and not badger me all the time, because it isn’t going to do any good.”

…before that…while I was in college, I went to the rector of the church I’d been raised in, and I said, ‘I want to disaffiliate with the church. I want to officially drop out. How do I do it?” and he said, “There is no way. You cannot do it.” And I said, “Oh. Fine. Then it doesn’t mean anything that I’m said to be part of the church. If there’s no way to get out of it, then it’s meaningless.”

In the mid-1970s my mother had a form of religious conversion; since then she has continued to be both a spiritual seeker and a committed political activist with particular focus on reproductive rights and US policy in Central America. (I diaried about one aspect of her life here). She is a member of the First Congregational Church (UCC) of Amherst, MA. We mostly don’t talk about religion (mostly because I don’t usually feel like it), but she knows that I’m a happy atheist (since that’s how she raised me). Most of the time she’s fine with it; once she voiced regret that my brother and I had not been raised with access to the comforting rituals and community engagement of a church. I said that while those things had been important for her childhood, they held no allure for us…and that a religion-free childhood was one of the greatest gifts she and my father gave us.

My father’s parents were Russian Jews who came to America in the hope of a better future. My father, the youngest of five children and the only boy, recalls that his father, who arrived in the US in 1903…

…was a very logical man. For him, there was always mechanism, and the task of the person is to discover mechanism. So when I was very very young, he subscribed to Popular Science magazine, and if I said “how does it work?” he’d say “Well, go read about it.” and popular science did not say “Jove made it happen this way.” they would say “The water weighs more on the wet side of the watermill than on the dry side, so the wet side falls,” and one learned that for each observed phenomenon there was an underlying mechanistic cause, and if you didn’t know it, you didn’t dream up something unless you could test it. The idea was, “See if it flies!”

When he came [to this country]…he felt “foreign,” so he thought, “Well, you have to figure out what makes an American American,” so he actually went over to the local school and spent…an hour or two in first grade, maybe a day in third grade, and he eventually spent time over the course of the school year in each of the eight grades of the primary school.

I think that being Jewish in Russia was not a nice thing. And [in America] religion did not play a formal role. In other words you were not identified as being a this or a that unless you chose to be, and that gave him the opportunity of not identifying himself as anything. That’s to the best of my understanding how it came about that I was raised in a non-theologically oriented or educated household.

At that end of Cambridge, virtually everybody was Catholic. …So most of my friends were Catholic, there were one or two Italians, mostly Irish Catholic…We didn’t particularly discuss it at home; there was no mention of religion at all. In a sense, that was highly advantageous, because I grew up not rejecting god, but just never having committed the fallacy of believing it…

When I was about five or six…one of [our neighbors] said to Mother, “Elizabeth, don’t you think it’s time that John began attending Sunday School?” and Mother replied, “If I were going to send him to a religious school, it would be a shul.” To which there was no reply. I don’t even know whether Miss Perkins understood what Mother was saying, because they were… innocent of Judaism and they obviously did not consider [our] family to be Jews. But that was all that was spoken on both sides, and everything continued as it was.

So it was clearly deliberate on my parents’ side…they didn’t want the children to mess with any religion. So it was simultaneously an abandonment, with respect to the outside world, of Judaism, and the desire not to be painted with any color.

The Roman Catholics routinely thought of all Jews as “Christ-killers” — so if there was a battle, there obviously was a vague perception that I was Jewish. Nobody ever asked, and I would…I denied it, because I was not anything religious.

…the issue never came up with [my] older sisters, because they, very carefully, made sure that it didn’t come up. And as a result, they essentially painted the picture in which I was born.

Consider the period, the epoch in which the other girls grew up. This was an epoch in which anti-semitism was rampant…So there was a good reason to conceal. So from that point of view it is fully understandable to me why they suppressed any connection whatsoever to being a Jew, to Judaism, to anything… So I was raised in a state of neutrality in which no religion was mentioned.

In which I briefly discuss our family’s tangential relationship with Organized Religion

There were occasional points when we bumped up against the demands of religious convention. When my brother and I were very small, my mother’s parents wanted us to be baptized. My father considered it irrational and superstitious. But as my mother recalls:

I couldn’t see any harm in it. And [your father] was so upset about it that I said, “Gee, you must think it affects the baby, if you feel so passionately about it. I think it does nothing to the baby, but it does a great deal to my parents, and I don’t want to hurt my parents so terribly when it doesn’t affect the baby.” …and he could see the logic of that, so he stepped aside, and you were baptized.

We celebrated Christmas, with a decorated tree, stockings hung by the chimney with care, and family visits. But the only time anyone ever said grace at our table was when my mother’s parents came to visit at Christmas or Thanksgiving. There was a regular carol-singing event outside a church in Sudbury, where my aunt and uncle lived, and we participated. I suspect that I sang more lustily on the songs where “Christ, our Savior” was not mentioned. I did not want to sing something I didn’t believe in; while I was too young to articulate what I felt, it clearly made me uncomfortable.

But our atheism was not something we discussed outside the house to any extent. It was simply that we never asked anyone about their religion, and nobody, to my recollection, ever asked us about ours.

In which I discuss the modeling of ethical behavior in my family, and how it has guided my ethics.

I asked my father for his thoughts on ethics:

My own philosophy about that was that ethics is admirable for its own self, because…ethics and morality are the lubricants that make a friendly society possible. So there’s no need to bring in religion. Religion teaches it as one teaches arithmetic: you learn the multiplication table, but that doesn’t mean you actually understand what’s going on, so that you really are ethical….so being taught that it is because “God said this,” “Christ said this,” “somebody else said that”…is no reason at all. One of the most telling things (which demonstrated, I think, that we had done something right) was a time…when we were coming back from the doctor’s, and you threw a candy wrapper out the window.

This incident has now become a deeply embedded piece of family lore. As my father recalls, I tossed a piece of paper out of the car window as we drove along. My parents stopped the car, and got out to retrieve the litter. Endeavoring to explain why I’d done something wrong, my parents asked, “What would the world look like if everyone threw paper out the window?” To which I replied, “Snow!”

In conversation with my dad, I pointed out that I might have been gleefully anticipatory rather than remorseful, and he agreed:

It doesn’t necessarily suggest that you were about to save the world from a snowstorm of trash, but to me it marked the difference between being a child and being a member of society. In my view, that’s how morality and ethics should be taught: “What would happen if everybody did this?” And then you don’t need to learn it as a catechism; you conclude that this kind of behavior is good for society and this kind of behavior is not.

I asked my mother about the same incident. She replied:

We didn’t talk with each other about teaching ethics, but I assumed that of course, that would just be part of growing up…not that “Now we’ll sit down for an ethics lesson!” But that would be exactly like that incident that you had mentioned. And I would say “Well taught.” You [and your brother] are both very ethical people, I think.

My mother and I used to hike a lot together. She greatly enjoyed the outdoors, and we frequently spent weekends in New Hampshire or Vermont, enjoying the forests and mountains. One of her regular directives was that I should “take nothing but pictures; leave nothing but footprints.” Further, it was understood that we would make a point of picking up any litter that had been dropped by others; we would sometimes take a plastic bag for this purpose. She would note that people who degraded the commons were at best thoughtless and at worst boorish and ignorant.

That was an example of their approach to ethics; what I later came to understand as the “categorical imperative.” They never mentioned Kant, but the broad application of this principle informed everything they taught me and my brother about correct and ethical behavior: if everyone acted this way, what would the world be like? And if nobody acted this way, what would the world be like?

Thus: pick up your trash, because if everybody picked up their trash, there wouldn’t be any litter making the landscape ugly. Don’t steal , because if everybody stole, stores would have to close and nobody would trust one another. Don’t lie, because if everyone told the truth, people would be much harder to mislead and manipulate. Think before you speak, because if everybody did that, people would speak more carefully and thoughtfully.

These principles informed the way they told us about, for example, the civil rights movement, and about the women’s rights movement. The sixties. Whew. There was certainly no shortage of “teachable moments” during those beautiful and terrible days.

Now, I make no claims to perfect application of these principles. Anyone who knows me knows that I’m sometimes thoughtless, unkind in my speech. When I was a teenager I shoplifted a few times. I have told lies; I’ve gossiped; I’ve failed to respect those who deserved respect, and occasionally groveled before those who deserved none. I have compromised for the sake of comfort, and I have been rigid and inflexible when there was no need for it. Yadda, yadda, yadda. My point is not that being an atheist makes you a “sinless” person, except in the sense that my family’s particular brand of atheism never used the word “sin.”

No, my point is that, thirty-five years after I spoke hurtfully to someone at a youth group meeting, I remember the incident vividly and with deep regret. I don’t need a theistic worldview to make me feel guilty; I feel guilty because I did a shitty thing to someone, and I’ll carry that knowledge with me till I die. The only person who can forgive me is the person I mistreated, and that’s the way it is.

I remember stealing a paperback book, back in the early 70s. I surely wish I could undo that; the knowledge of a misdeed lingers in the mind. I do not think of myself as damned; nor am I in need of a soteriological solution to my guilt. I made a mistake, way back then, and I learned from it and continue to learn from it. How do I know I’m learning from it? Because I continue to remember it with regret; because I still feel guilty.

And I’ll say it again: I don’t feel guilty because I sinned, and God is disappointed. I feel guilty because I did something which made the world an infinitesimally crappier place to live.

One thing I never felt guilty about was masturbation.

When my brother and I were getting into the puberty years, my mother dealt with a lot of the questions of sex in a very matter-of-fact and non-guilt-inducing way. She was (and is) an excellent artist, and at one time had considered a career in medical illustration.

She took out her colored pencils and drew accurate, anatomically correct, inside and outside views of the human reproductive anatomy. Then we got a detailed explanation of how all the parts worked. We always considered her drawing ability sort of miraculous to begin with, and to have her providing us with the straight dope on all the stuff our peers had been speculating about…well, that was just amazing! We became, briefly, the go-to guys for the facts of life.

That was, of course, just part of the discussion. As we grew to an age where it was increasingly likely that we would be sexually active, my parents reminded us that we had a responsibility to use contraception, and to treat our partners with respect.

It was embarrassing, of course, since I hadn’t had any partners yet…and of course, later on those admonitions didn’t stop me from being a hormone-crazed teenager…but y’know, looking back on it at age fifty-one, I think I did okay. I never got any social diseases and I never caused any pregnancies. The relationships I had were pretty equitable, and while there are some I regret, there are also many I remember with warmth and affection. And, of course, I knew that the only damage I could do when I was by myself was, um, chafing. God, Jesus, Ceiling Cat, FSM? Nobody was watching; nobody cared what I did with my sticky-outy-bits.

In which an alienated teenager becomes affiliated with (gasp!) a church group and meets many, many, many more atheists there.

In 1974, I wound up going to a summer camp that was loosely affiliated with a church. Fortunately, the church was the Unitarian Universalists, and the summer camp was Rowe Senior High, in Rowe, Massachusetts.

The feeling I got when I first arrived at Rowe was…well, the best analogy I can give is that it was like the feeling I got when I discovered Daily Kos, back in 2006. Oh! There are people like me in the world! I am not alone! I like these people, and I like being here!

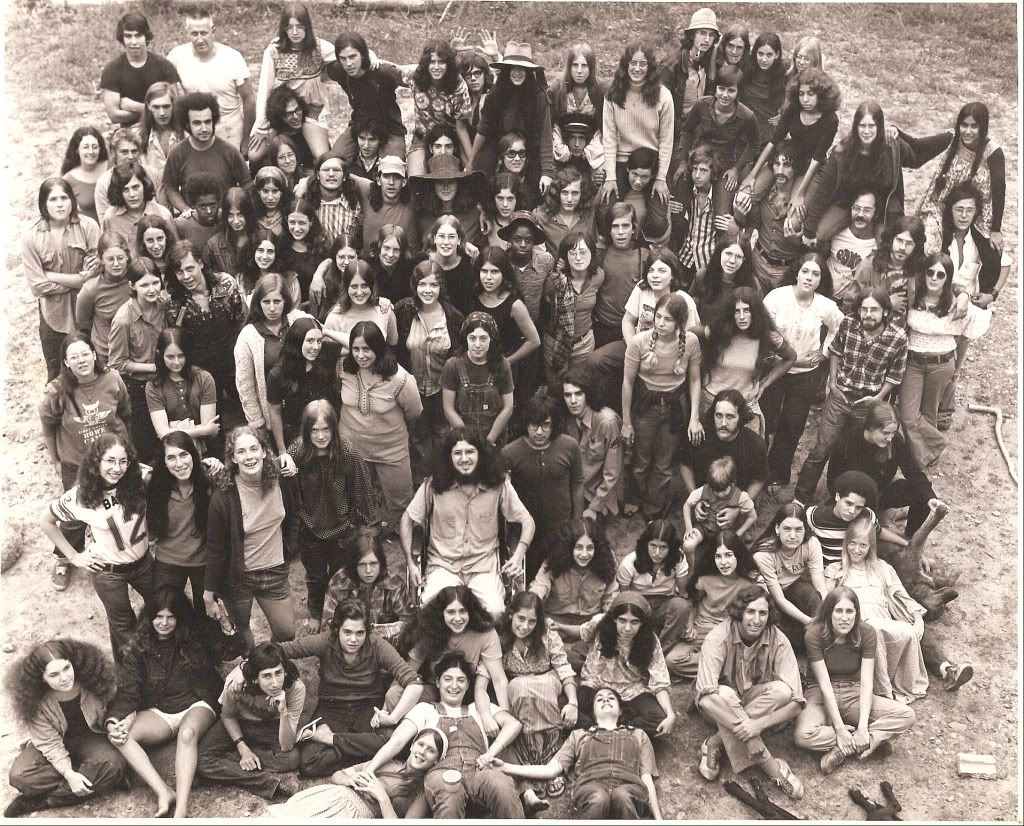

A Rowe Senior High group portrait. The man in the wheelchair is my friend Mark Reich, about whom I wrote here.

I didn’t know much about the UUs, but many of the campers were also members of a (now-legendary) youth group which was a part of the Unitarian Universalist organization. And, fascinatingly, those were the folks with whom I felt the greatest unity of sentiment. After my first summer at Rowe Camp, my friend Jack (who was, I knew, an atheist, because we’d had that discussion late one night while drinking very bad coffee from the giant urn in the Rec Hall) said, “Warren, you should get into LRY.”

“What’s LRY?” I asked.

“It stands for Liberal Religious Youth,” he replied, “and it’s like Rowe Camp, only more so. LRY has ‘conferences’ all over the country, and the people are amazing. You’d love it.”

We hitchhiked together to my first LRY conference, which was in Durham, North Carolina. It was August, 1974, and this was the yearly “Continental Conference,” to which literally hundreds of young people came by car, bus and thumb from all over the country.

And I did, in fact, love it. There were more atheists in one place than I’d ever imagined. There were people who were just as alienated in their hometowns as I was in mine…people who were, well…aw, bigbangit!… hippies. And not, for the most part, dumb hippies. These were hippies who were paying attention. And this was August of 1974, and as fate would have it, it was during that week that Richard Nixon resigned. And man, oh, man! There were people cheering and clapping and dancing; it was great.

Group photo from a 1977 LRY conference. I’m in there somewhere.

Incidentally, I found out years later that LRY was on Tricky Dick’s “100 most subversive organizations” list. How cool is that?

But I digress. One of the features of both Rowe Camp and the LRY gatherings I attended was what were called “worship” services. These happened every night; attendance was entirely optional. Over the years that I participated, I never heard anybody mention God or gods except in passing. Nobody spoke of salvation, or damnation. People talked about questions they found important, shared music they loved, created “rituals” in which all present participated. Once, somebody played John Coltrane’s “OM” in its entirety (a lot of people left before that one ended — the recording is forty minutes long and filled with cacophonous saxophone shrieking — I loved it, needless to say).

I got interested. These “worship” events were essentially multi-media performance art with a transcendentalist slant (we were hippies, remember). I began volunteering to run them, and for a few years I organized many worship services at LRY conferences on the East coast. Hitchhiking to whichever church or community building was hosting the gathering, I’d bring a mirror and some lighting equipment (for ad hoc light shows), some recordings of unusual music or sounds, and some sources of inspirational, enigmatic or simply beautiful text. Then I’d put them all together in the evening. Once it was Terry Riley’s “In C,” and once it was the result of three hours playing with a friend’s reel-to-reel tape-recorder, creating a multi-tracked drone fantasia with slowed-down voices reading passages from Italo Calvino’s “Invisible Cities.” It was fun. Further, it allowed me an opportunity to convey some of my own perspectives on “spirituality” and “spiritual experience.”

The fact that I (an admitted atheist who was unaffiliated with any church — even a UU chapter) was encouraged to direct “worship” services for my peers at LRY conferences says a lot about the UUs and about LRY. The fact that I wanted to do it says a lot about me, and a lot about the particular version of atheism I inhabit.

In which I discuss my own personal relationship with “spirituality.”

God or gods are not, to me, in any way connected to the experience of “spiritual awe.” God or gods may be the way that some people experience a connection with spiritual awe, but that strikes me as an important distinction. You may experience a connection with your mother when you’re talking to her on the phone…but the telephone is not your mother. Spiritual awe is what happens when humans confront things that are too big or too small for their perceptions; spiritual training is, I think, the development of perceptual faculties infra or ultra to our normal perceptual set.

For me, there are three things that consistently evoke spiritual awe: deep time, the natural environment, and music. When I contemplate the total life span of our universe, I am staggered and silenced. When I walk in the woods, I am reminded of my own membership in the world’s community of life, and my responsibilities to it. When I sing, when I hear other people sing (even when they’re out of tune) I am similarly staggered (although not necessarily silenced). I remember reading (in the Cowells’ biography) Charles Ives recalling his father George:

“Once when Father was asked: ‘How can you stand it to hear old John Bell (who was the best stonemason in town) bellow off-key the way he does at camp-meetings?’ his answer was: ‘Old John is a supreme musician. Look into his face and hear the music of the ages. Don’t pay too much attention to the sounds. If you do, you may miss the music. You won’t get a heroic ride to Heaven on pretty little sounds!’ “

My mother tells me that when I was about six or seven, she found me huddled over one of those Time-Life books: “Our Universe.” I was crying. She investigated and found that I had been carefully studying the page which depicted the death of the sun: its final stages as a red giant and a white dwarf. She tried to comfort me by saying, “Don’t be scared. That’s not going to happen for a long long time,” but (according to family legend) this only intensified my crying. “No, no, no!” I sobbed. “I want to see it happen!”

I rely on all three of these things for my own framing of ethics and morality.

Analyzing one’s own behavior or the behavior of others in different time-scales provides a more robust way to link ethical behavior to long-term sustainability. Can we begin to think more than seven generations ahead? Behaviors that will reduce humanity’s chances of survival, or which will damage the fragile web of biodiversity which sustains us all, are intrinsically unethical. To pay attention only to the short term is a moral failing.

To behave in a way that recognizes, respects and celebrates our membership in the global web of life is to behave ethically. Now that the planet Earth is humanity’s ecological niche, it is both ethical and essential to consider as many biological links outward from ourselves as we can.

Musical phenomena offer me a set of metaphors and analogies which clarify the implications and qualities of my behavior or the behavior of others. To be “out of tune” or “out of time” is a failure to listen carefully to one’s environment; we see daily the extent to which conservatism listens only to its own voice, failing to hear the grating dissonance between its notes and those of the rest of the country and the world. To be “in tune” or “in time” is to surrender a certain degree of one’s own autonomy for the greater good; as anyone who has sung in a chorus or played in a drum circle can tell you, this may be a form of “surrender,” but it is one that is ultimately profoundly ennobling and empowering.

And what about when I die?

When I wax eschatological, I move easily between various possibilities.

The first is simply that I will end. Once the physical substrate which carries my consciousness shuts down, so will that consciousness. From there on, it’s just…nothing. Which doesn’t scare me, particularly, aside from the fact that I’ll never get to see how things turn out. It does motivate me to do the best I can in the time available; to influence others to live simply and sustainably and in accordance with the principle of right livelihood.

Another possibility, to which I alluded earlier in this diary, is that I will “rejoin the great hum of the universe.” I don’t know what that means, really; it’s just a comforting thing I say to myself when I don’t want to wrap my mind around the thought of just…ending. I do believe that at some level, everything is vibration, and if my own consciousness ends by merging with all the other vibrations that are…well, that sounds just fine to me.

The third is an analogy which rests on my pathetically inadequate understanding of the physics of black holes. An observer watching an object fall into a black hole would see it slowing down and eventually remaining motionless as it reached the Schwarzchild Radius. I postulate that the physical shut-down of the body and brain is analogous to falling into a black hole. The self-awareness of the individual, in this analogy, is the watching observer; as consciousness approaches extinction, it gets closer to the cognitive analogue of the Schwarzchild Radius, eventually slowing to a standstill. Where it remains forever.

And if you’re going to be stuck inside your own solitary consciousness forever, it is incumbent on you to lead a life that you can recall without too much shame and sorrow.

See? An explanation of post-mortem survival of identity that requires no deity. It’s probably nonsense, but so what? It’s something I think about from time to time, and it helps remind me to lead a life I can imagine recalling without anguish and regret for all eternity.

Pete Seeger’s beautiful song expresses what I feel when I contemplate my death:

To My Old Brown Earth

To my old brown earth,

and to my deep blue sky —

I’ll now give these last few

molecules of “I.”And you, who sing —

and you who stand nearby:

I do charge you

not to cry.Guard well our human chain;

watch well you keep it strong,

as long as sun will shine……and this, our home —

keep pure and sweet and green,

for I am yours,

and you are also mine.

In which my music teacher clarifies an important point.

I am by profession an Indian classical musician; I perform and teach the songs of the North Indian “Hindustani” tradition. In order to learn this style of music, I became the disciple of a master teacher, Pandit S.G. Devasthali, of Pune, India. I studied with my Guru for many years, using the time-honored techniques of oral/aural transmission.

One day I asked him, “Guruji, I am not a Hindu; in fact I am an atheist. How can I reconcile the singing of songs on Hindu religious themes with these facts?”

He responded, “If you sing a song in which Krishna or Rama is mentioned, substitute in your own mind whatever seems appropriate. You need not feel any conflict. No two people mean the same things when they sing these names, and you can make ‘Rama’ or ‘Krishna’ mean anything you wish.”

I said, “That makes sense. Thank you.”

Incidentally, I later found that there is an atheistic branch of Hinduism, called Chaarvaaka, which “assumes various forms of philosophical skepticism and religious indifference.” It would not surprise me if Pt. Devasthali were an adherent; he described himself as “a staunch Hindu” while treating the claims of religious leaders with contempt. Saying, “work is my worship,” he composed, performed and taught songs on both Hindu and Muslim texts throughout his career.

He composed a “bhajan” (devotional song) which I enjoy singing:

Repeat “Om.” Renounce ego.

Don’t regret; what’s done is done.On seeing the suffering of any person, offer succor.

Don’t be proud or arrogant; uphold your dharma.When you can, do a good deed;

Until this moment you have been asleep.Renounce bad thoughts and immorality;

Don’t be self-centered in the intoxication of youth.Do good deeds from your heart, mind and soul;

So much of your life has been wasted.Rama says this; Krishna says this:

Don’t unknowingly do harm to anyone.Zarathustra says this; Jesus also says this:

Love all in the world.Allah says this; Eeshwar also says this:

Don’t make quarrels between different religions.Repeat “Om.” Renounce ego.

Don’t regret; what’s done is done.

In which I consider what to do now that I’m a parent.

In 1986, while living in India, I met Vijaya. Two years later we were married. In 2005 our daughter Sharada was born.

My wife, in her own words, is “atheist, agnostic and Hindu.” Her family is Hindu, and to the extent that we reference a religious tradition, it is Hinduism. My wife and I both sing songs on Hindu themes around the house; I, of course, teach them to my students every day. The little one loves these songs and has been singing them sotto voce to herself more and more. We have some children’s books on Hindu legends, and they’re frequently requested — “Mommy! Please read me ‘Boogie Woogie Ganesha’!”

We celebrate Christmas. Sharada loves to help decorate the tree. Eventually she’ll ask for more explanations.

This year we had a holiday over Easter. On the way home from school, we had the following colloquy:

Daughter: “Daddy, why is there no school tomorrow?”

WarrenS: “Tomorrow is a holiday, sweetheart.”

D: “What’s a holiday?”

W: (thinking frantically) “People everywhere love to tell stories to one another, darling. People in our part of the world have a story they love very much, and so they decide that they’ll have a special day when they’ll all tell that story to one another. That’s a holiday.”

D: “Oh.”

W: (breathes huge sigh of relief).

When it’s time to talk about religion, I’ll tell her something like this: “Human beings tell stories to one another to make sense of their world. Because they are stories, the characters can do anything the storyteller wants them to. Some of them can fly, or live forever, or control the actions of others, and they’re often important characters in world-explaining stories. A “god” is a character in a world-explaining story who can do things human beings can’t…and there are as many gods as there are stories.”

We have been taking her on nature walks. The other day the two of us were out in a nearby forest, turning over rocks and watching the insects scuttle for cover. I said, “Sharada, there is life everywhere! Under every rock there are little bugs and worms! In the rotten log there are ants and slugs and moss! Everywhere you look, there is something alive, doing its work. Isn’t it wonderful?”

On our way home we heard a rustling from the underbrush. We stopped, and I looked for the source of the noise. When I saw what it was, I confess I almost said, “Nothing to see here, move along, move along.” But in the event, I chose to call her attention to it:

WarrenS: “Sharada, look! There is a snake, and it’s in the middle of eating a big toad!”

Daughter: (looks, wide-eyed) “Is the toad dead?”

W: (gulps a little) “No, sweetheart. It will be dead soon, but right now it’s still alive. You can see it breathing.”

D: (turns away) “Oh, the poor toad!”

W: (gulps some more, cudgels brain frantically for something to say) “Well, yes. It is sad for the toad. But remember that now the toad will become part of the snake. And perhaps a bird will catch the snake and eat it, so the snake will become part of the bird. And perhaps the bird will die and fall on the ground, and bugs will eat it. So the bird will become part of the bugs. And perhaps a toad will come along and eat the bugs, so they’ll become part of the toad. We are all part of the Earth; we all come from the Earth and we will all go back to the Earth.”

D: (remains silent and thoughtful for a long time as we walk home)

That afternoon she told her mother what she had seen, and recited back the simple version of the cycle of life I’d given her.

My wife and I are bringing our daughter up to love and respect the world and its community of life. We will be bringing her up to live ethically, creatively, empathically and gracefully. She will be whatever she wishes to be.

I was fortunate in that my atheism was not a rebellion against some form of imposed belief system; I bear no grudge against The Church for lying to me, since I didn’t grow up hearing any lies. I grew up without fear of supernatural forces (unless you count a sleepless night after watching “Bride of Frankenstein” on late night TV when I was eleven). I hope that we can help our little girl grow up without irrational fears…and I hope that by the time she is old enough to read these words, people like her father are no longer irrationally feared and hated by the majority of our country’s population.

—————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

Originally posted at Daily Kos: Link

LRY FOREVER!!!!

I found this to be an interesting read. I have found nothing that I disagree with however I would like to add that atheism seems to be predicated upon the concept of dualism. This is the belief in a fundamental separation between creator and created. But many Hindus, Buddhists and other followers of Eastern religions believe in non-dualism. A non-dualistic definition of god makes Atheism problematical, because denying the existence of god, also denies the existence of the material world. I think that most people would find this paradoxical

I found your blog through the Allen West Facebook page comments. I enjoyed reading your story, thank you for sharing it.

Love the post, look forward to reading more.

Well, if “god” is just a word for “everything,” then I agree, there’s no problem. But that’s not how an awful lot of people understand the term, including plenty of adherents to various Eastern belief systems.