India Indian music music: genius violin

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

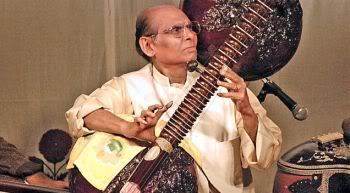

78 rpm Records of Indian Music: Pandit V.G. Jog, with Ustad Ahmed Jan Thirakwa

Two early recordings of the late Pt. V.G. Jog, one of the musicians who made Hindustani violin a force to be reckoned with in the 20th century.

Pandit Vishnu Govind Jog, better known as V. G. Jog (22 Fehruary 1922 – 31 January 2004), was an Indian violinist. He was the foremost exponent of the violin in the Hindustani music tradition in the 20th century, and is credited for introducing this instrument into Hindustani music.

Jog was a disciple of Baba Allauddin Khan. He performed and recorded with many of the greatest Hindustani musicians of the 20th century (including Bismillah Khan) and toured the world. He frequently performed for All India Radio’s Calcutta division. He received the Padma Bhushan award in 1982.Wiki

He is accompanied by one of the greatest exponents of tabla ever known in India, the late Ustad Ahmedjan Thirakwa:

Ahmed Jan Thirakwa Khan was an Indian tabla player, commonly considered the preeminent soloist among tabla players of the 20th century, and among the most influential percussionists in the history of Indian classical music. He was known for his mastery of the fingering techniques and aesthetic values of various tabla styles, technical virtuosity, formidable stage presence, and soulful musicality. While he had command over the traditional tabla repertoire of various gharanas, he was also distinguished by the way in which he brought together these diverse compositions, his reinterpretation of traditional methods of improvisation, and his own compositions. His solo recitals were of the first to elevate the art of playing tabla solo to an art in its own right in the popular mind. His style of playing influenced many generations of tabla players.

A meeting of the titans, indeed. Enjoy these two performances, probably from the early 1950s.

This version of Raga Bahar is based around the popular chiz Phulwaale kaunt main ka basaunt, recorded in the 1920s by Narayanrao Vyas.

Raga Nat Bihag; inevitably, this is an adaptation of the canonical chiz Jhan jhan jhan payal baaje, sung by pretty damn near everybody who’s ever performed this raag.

Thirakwa is rock-solid and authoritative throughout these performances.

India Indian music music vocalists: genius khyal

by Warren

3 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

More Early Mallikarjun Mansur To Delight Your Ears

Three more gems from Buwa’s Gwalior period, for your enjoyment:

“Karnataka Kafi”

==========================================

Raga Puriya

==========================================

Raga Brindabani Sarang

India Indian music music: genius Hindustani instrumentalists Raga

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

78 rpm Records of Indian Music: Abdul Aziz Khan

I’m gradually getting more of my collection of Hindustani 78 rpm records digitized and uploaded.

Here are two performances by the vichitra veena player Abdul Aziz Khan, of the ragas Darbari Kanada and Bageshri.

On both recordings the Ustad can be heard giving himself daad when he plays something nice. It’s a fascinating look at the artist’s mind in its relation to the listeners; he needed to have rasikas enjoying his music for it to have any meaning — and since it was just him and the tabla player in the room, he provided his own feedback as needed.

More to come. I have hundreds of these recordings and I plan on getting them all uploaded in the next year or so.

Indian music music vocalists: genius khyal

by Warren

3 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Faiyaaz Khan: Aftaab-e-Mausiqi

Raga Darbari Kanada

==========================================

Ustad Faiyaz Khan is so far the best known exponent of Agra Gharana in Hindustani classical music. He was the master khayal vocalist of his time. Born at Sikandara near Agra in 1886 (contested as 1888, 1889)[1], he was the son of Shabr Hussain, who died three months before his birth. He was brought up by his maternal grandfather, Ghulam Abbas (1825?-1934), who taught him music, up to the age of 25. He was also a student of Ustad Mehboob Khan Darspiya, his father-in-law and was a for short time a disciple of Ustad Jagadguru Mallick of Calcutta who had the famous sarodiya Ustad Hafiz Ali Khan and the renowned sitarist Ustad Enayet Khan in his tutelege.

WIKI

An extraordinary performance of Raga Desh.

==========================================

The vocalist and historian Susheela Misra writes:

Faiyaz Khan’s musical lineage goes back to Tansen himself. His family is traced back to Alakhdas, Malukdas and then to Haji Sujan Khan (son of Alakhdas who became a Muslim.) Genius, musical ancestary, and training combined to give us this wonderful artist-one of the most reputed and respected exponents of Hindustani classical music in recent times. He had the exceptional good fortune of receiving his talim in Dhrupad singing from his grand father, Ghulam Abbas Khan; and in Dhamar from his grand uncle, Ustad Kallan Khan, both of whom were leading musicians of the rangila gharana in the second half of the last century. Kallan Khan was the younger brother of Ghulam Abbas Khan and, therefore, the grand-uncle of Faiyaz Khan Sahib. Ghulam Abbas Khan was his maternal grandfather, and Rangeela Ramzan Khan his paternal great grandfather. Faiyaz Khan’s uncle, Fida Hussain was a court musician in Tonk (Rajputana). Faiyaz was born at Sikandra near Agra in 1880 and he died in Baroda on 5th November 1950. As his father Safdar Hussain died very early, his grandfather adopted him and brought him up as his own son. Ghulam Abbas Khan, the son of the great Ghagge Khuda Bux and an intimate friend of Bairam Khan, not only imparted to the boy the authentic taleem of his gharana, but also took the promising young Faiyaz on a “pilgrimage of music”, visiting all the important centres of music, listening to great contemporary musicians, and bringing him practical experience in concert singing. By the time he was 18, Faiyaz Khan had become such a “polished” artist that he began to give recitals in places like Bombay, Calcutta and Gwalior. Once at Bombay, 24 year-old Faiyaz got a chance to hear the great Miyanjan Khan, a pupil of the great Fateh Ali Khan of Patiala. Immediately after him, Faiyaz was asked to sing. At first he copied Miyanjan Khan’s Multani in the latter’s style and then he demonstrated in his own style-both in such a masterly way that Miyanjan Khan embraced the young singer and exclaimed in genuine appreciation: “Tum hi ustad ho” (you are a true descendant of the masters of the art.) It was an age of gentlemen-musicians. Link

==========================================

The canonical chiz in Raga Chhayanat, Jhanana jhanana.

==========================================

While people used to admire his flawless diction in Urdu, Hindi, etc, they used to be amazed at his graceful and fine pronunciation of Braj-Bhasha in which a large number of Khayals, Dhamars, etc, are couched. This was because Faiyaz Khan spent his early years in the Braj-Bhasha areas like Mathura, Agra, Atrauli, etc. His father-in-law, Mahboob Khan of Atrauli, was none other than the reputed composer Daras Piya whose khayals in ragas like. Jog, Anandi, etc, are still so popular. Another relation–Suras Piya- was a wellknown composer who lived a recluse’s life in Mathura.

The song Man Mohan Brij ko Rasiya (in Paraj) which Faiyaz Khan has made famous, is a sample of Saras Piya’s compositions. Faiyaz Khan himself composed many songs under the penname Prem Piya.

In his youthful “halcyon days” Faiyaz Khan sat in the company of great artists like Moizzuddin, Bhaiya Ganapatrao and Malkajan. That was how he had imbibed the romantic Thumri style and could render Dadras and Ghazals so imaginatively. Many a time I have witnessed Faiyaz Khan rendering the Bhairavi Thumri “Babul Mora” and drawing tears out of the listeners’ eyes. Faiyaz Khan used to say that Malkajan’s Bhairavi-Thumris were peerless. And Malka even in her obscure later years never missed the Ustad’s concerts in Calcutta. Unlike some highbrow musicians, Faiyaz Khan never looked down on light classical types of songs. He used to say:- “It is not a child’s play to sing a Thumri or a Ghazal. The essence is the bol-but one has to be very imaginative and original.” Even into a simple Dadra he could pour a lot of genuine emotion. Link

==========================================

Another “Payal baaje” bandish, this time the classic in Nat Bihag.

==========================================

Ramkali: Un sanga laagi ankhiyan. His layakari is very enjoyable.

Ustad Faiyaz Khan would render a full scale ‘Nom-Tom’ alap and follow it up with khayal compositions, thus blending dhrupad and khayal and giving his gayaki more flexibility. His bol-banawo, bant, layakari, and his inimitable style of reaching the sam are unmatched even today. He was a great composer himself, his pen name being #145;Prempiya’. His compositions in raga Jaijaiwanti, Jog etc. are treasured by Agra singers to this day. In fact, Faiyaz Khan’s Agra gayaki became so famous that most of his students and followers would actually copy him to the very last detail, imitating even his voice.

Baju band khul khul jaaye in Raga Bhairavi. One of the pivotal renderings of a timeless classic. Enjoy his layakari and occasional tappa-ang taans in the laggi section.

Another Bhairavi, Banao batiyaan. This wonderful dadra performance is packed with emotion. Note his heartfelt pukaras as he approaches the top Shadja; nobody can evoke emotion like this anymore, alas. Also notice his inclusion of vernacular, “speechy” utterances like “Aare haan” (“Oh, yeah!”) in the course of his rendering, rather like a contemporary bluesman.

Jazz music vocalists: genius Great American Songbook

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Hoagy Carmichael

The composer of countless wonderful songs was also a charmingly relaxed performer of his own music. In the second half of his career he was often given cameo roles in movies, performing one or another of his contributions to the Great American Songbook.

—————————————————

Lazy Bones

==========================================

Hoagland Howard “Hoagy” Carmichael (November 22, 1899 – December 27, 1981) was an American composer, pianist, singer, actor, and bandleader. He is best known for writing “Stardust”, “Georgia On My Mind”, “The Nearness of You”, and “Heart and Soul”, four of the most-recorded American songs of all time.[1]

Alec Wilder, in his study of the American popular song, concluded that Hoagy Carmichael was the “most talented, inventive, sophisticated and jazz-oriented” of the hundreds of writers composing pop songs in the first half of the 20th century.

WIKI

==========================================

Am I Blue

==========================================

He was born Hoagland Howard Carmichael in Bloomington, Indiana on November 22, 1899. His father was an electrician and his mother played the piano for dances and silent films. Although his ambition was to become a lawyer, Carmichael showed an early interest in music. When his family moved to Indianapolis in 1916, he took lessons from an African-American pianist Reginald DuValle. He attended Indiana University, and, while there, he organized his own jazz band. When the great jazz cornetist Bix Beiderbecke, then at the very beginning of his brief career, paid a visit to Indiana University in the spring of 1924, he and Carmichael quickly became friends, and it was for Beiderbecke that Carmichael wrote his first piece. Not long afterward, Beiderbecke and the Wolverines recorded it under the title “Riverboat Shuffle”.

Carmichael went on to the Indiana University Law School, and continued to perform and write music while there. He graduated in 1926, and began to practice law in West Palm Beach, Florida. However, the discovery that another of his early tunes “Washboard Blues” had been recorded prompted him to abandon law for music. He briefly returned to Indiana, and then in 1929 he arrived in New York. He resumed his contact with Beiderbecke and was introduced with some of the most talented young musicians of the day, including Louis Armstrong, the Dorsey Brothers, Benny Goodman, and Jack Teagarden. Another important lifelong friendship during this time was also established with lyricist Johnny Mercer. Link

==========================================

Playing “Stardust” — next up is Hoagy’s vocal version from 1942:

Hoagy’s whistling is great.

==========================================

Here’s a discography of some of Hoagy’s own recordings.

==========================================

Lazy River, from 1930.

==========================================

Old Buttermilk Sky. In last year’s “Singing For The Planet” concert, Dominique Eade performed a beautiful version of this song.

==========================================

“Old Rockin’ Chair,” a song originally written for Mildred Bailey. Recorded in 1956 with the Pacific Jazz All Stars.

==========================================

Carmichael was a Republican supporter and FDR hater, voting for Wendell Wilkie for president in 1940, and was often aghast at the left-leaning political views of his friends in Hollywood.

WIKI

Nobody’s perfect.

Education India Indian music music Personal: aesthetics Education genius India Indian music music obituary

by Warren

2 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

A Great Tree Has Fallen: Asad Ali Khan, R.I.P.

This Tuesday, June 14, the world of music lost a great spirit.

Ustad Asad Ali Khan, one of the few remaining performers on the ancient Indian stringed instrument called the Rudra Veena, passed away after suffering a heart attack in the early hours of the morning.

He performed an austere and sober style of music, an instrumental version of the vocal style known as Dhrupad, which dates back to the 11th century or so. The Rudra Veena, or Been, is considered to be one of the oldest instruments of Indian tradition; it has its own origin myth, which states that the instrument sprang full-blown from the forehead of a meditating Lord Shiva. It is interesting that Asad Ali Khan, whose name makes his Muslim ancestry evident, saw no religious conflict in embracing this story; ecumenicism in Indian musical traditions is alive and well.

Education music Personal: homeschooling math woodworking

by Warren

2 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

What Did You Learn In Unschooling Today?

Daughter and I had breakfast this morning, and she asked me some random addition questions. “Dad, how do you make twenty-seven?” It turned out she was thinking about a series of dance moves her Kathak classes had introduced, in which a group of nine turns is done three times. Her teacher had only shown the first two repetitions, so there was some confusion in her mind.

We worked it out; I was inspired to play some more with groups of nine, so we began adding up columns of 9s. All the fun of early math tricks started to come back for me — add up the digits of the sum of any group of nines, and they always add up to nine; etc., etc., etc. We kept adding nines together and exploring what the results looked like. Eventually I drew a 9×16 matrix on a piece of paper and filled in each cell as she counted up to 144.

She asked for some other numbers, and we played with 5s and 3s, examining the patterns they created as their sums built up. It was a fun way to prolong our breakfast.

Eventually she finished her oatmeal, and asked me to do more numbers. And I said, “I’ll give you a rhythm lesson.” She responded, “I don’t want a drum lesson now!” and I said, “Not drums. Rhythm and numbers.”

Whereupon I started showing her Reinhard Flatischler’s “TA-KI” and “GA-ME-LA” syllable groups.

We sat facing one another in two chairs. I said, “I’m going to say some magic rhythm words, and you say them back. The first word is TA-KI. Try it.”

She did. So we traded groups of recited TA-KIs back and forth for a while until she was comfortable with them. I began patting my knees on the first syllable of each TA-KI, and she imitated me happily.

Eventually I said “Great! The second rhythm word is GA-ME-LA. Try it!” and we repeated the process.

Then we started mixing up the syllables, while patting our knees on the first syllables of each “word.”

TA-KI / GA-ME-LA = 5 beats, accented 2+3

TA-KI / TA-KI / GA-ME-LA = 7 beats, accented 2 + 2+3

TA-KI / TA-KI / TA-KI / GA-ME-LA = 9 beats, accented 2 + 2 + 2 + 3

GA-ME-LA / GA-ME-LA / TA-KI = 8 beats, accented 3 + 3 + 2

She was getting it! While there were frequent glitches in the knee-patting, she recovered nicely.

Eventually we decided to do patty-cake. She really took the initiative at this point, deciding which syllable groups should have knee-pats, which should have patty-cake claps, and which should have spoken syllabic recitation. At this point I was just along for the ride.

The last few minutes were spent jamming on an 11-beat sequence, divided 3 + 3 + 3 + 2:

GA-ME-LA / GA-ME-LA / GA-ME-LA / TA-KI.

She decreed that we would pat knees for each of the GA-ME-LA groups, but not recite; on the final TA-KI, we’d clap each other’s hands and speak the “word” out loud. There we stayed for multiple repetitions, gaining confidence and competence.

Eventually we stopped and went upstairs, where she got dressed and ready for the next part of our day.

Which was spent in the woodshop. We’ve been making a stringed instrument together, and today was to be devoted to using my newly acquired drawknife for the shaping of the third tuning peg. The previous two had been very time-consuming, requiring chisels, surforms and a disc sander to achieve the right shape. But this tool, terrifying though it looks (a 10-inch knife sharpened to a razor edge in the hands of a six-year-old?), is designed beautifully. Harming one’s self is virtually impossible, since holding the handles prevents the blade from getting near arms, fingers, wrists or any body part.

And she loved it. “Dad! This is a wonderful tool!” She didn’t want to stop removing wood, and her hands grew steadily more intelligent with each stroke. “Can you give me some other pieces of wood so I can practice some more with the drawknife? Look! I’m getting to be really good at drawknifing!” (a wonderful verb, I think).

And soon the tuning peg was shaped correctly; a little rounding on the disc sander and it was just about the same shape as the others, which had taken easily four times longer to make. Sometime later this week we’ll finish stringing her “tar,” and start lessons.

And then we got on our adult-and-kid tandem bike and had a long ride, including a visit to Mom at work, a trip to the library, lunch, an ice-cream cone, Daddy getting a cappucino, a playground visit and a return home about four hours later.

A good day of homeschooling.

India Indian music music vocalists: genius khyal

by Warren

2 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Mallikarjunbua Before Jaipur-Atrauli Training

Here are some more of the 78 prm discs from Mallikarjun Mansur’s early period, when he was still singing Gwalior gayaki. These recordings are utterly delightful.

Gaud Malhar:

Jaunpuri:

Kafi:

Adana: