India Indian music music Personal vocalists Warren's music: concerts

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

I am performing khyal…

…a little later on today at the Chinmaya Mission in Andover, MA.

It’s been fun practicing although I have not really had enough time. Many of the techniques that I discuss in Posts About Practicing really come in handy here in the first part of the twenty-first century, with a kid and a house and a global climate crisis occupying my attention. Ten hours of practice a day, which I used to do back in India in the 1980s, really seems like a mythological accomplishment.

Full report later on…

India Indian music music vocalists: genius Kirana gharana

by Warren

4 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Sureshbabu Mane

This recording of the Bhairavi thumri “Baju band khul khul jaa” is really exquisite. Sureshbabu’s vocal quality is very much like that of his father Abdul Karim Khan, but there is a relaxed sweetness that is unique.

Sureshbabu Mane (1902 – 1953) was a prominent Hindustāni classical music singer of Kirānā Gharānā in India.

Sureshbabu was born as Abdul Rehmān to Kirana Gharana master Ustād Abdul Karim Khān and Tārābāi Māne. Tarabai was the daughter of Sardār Māruti Rāo Māne, a brother of princely Barodā state’s “Rajmātā” during the middle of the 19th century. Abdul Karim Khan was the court musician in Baroda when Tarabai was young, and he taught her music. The two fell in love and decided to get married; but Tarabai’s parents disapproved of the alliance, and the couple had to leave the state (along with Abdul Karim’s brother, Ustād Abdul Haq Khān). The couple moved to Bombay (Mumbai), and had two sons: Suresh or Abdul Rehmān, and Krishnā; and three daughters: Champākali, Gulāb, and Sakinā or Chhotutāi. In their adult lives, the five respectively became known as Sureshbābu Māne, Krishnarāo Māne, Hirābāi Badodekar, Kamalābāi Badodekar, and Sarswatibāi Rāne.

His pronunciation is very soft, a characteristic of many Kirana style singers who embodied the notion that clear articulation of the words detracted from qualities of intonation. This is a highly vowel-oriented style!

Sureshbabu was an avocational alchemist, a tragic hobby that may have contributed to his early death through exposure to toxic chemicals. It’s trite but accurate to remark that his real alchemy was in the realm of musical expression; I have rarely heard such a haunting version of this thumri.

I used to visit Hirabai Barodekar’s house in Pune fairly often when I was living there. She was a very old lady at the time; I sang for her once just after I’d arrived and she was kind and polite in her responses. Her grandson Nishikant Barodekar was on his way to becoming a very well-regarded tabliya.

If Complexion Is Insufficiently Wheatish, Just Adjust Your Monitor

Well. This is truly weird.

New Delhi: Indian bachelors keen to get a taste of married life can now log on and apply for a virtual wife online in a scheme that offers a glimpse into changing Indian society.

Bharat Matrimony’s biwihotohaisi.com (an ideal wife) website allows men to choose from four different types of wife and then receive automated telephone messages from them that reflect their character.

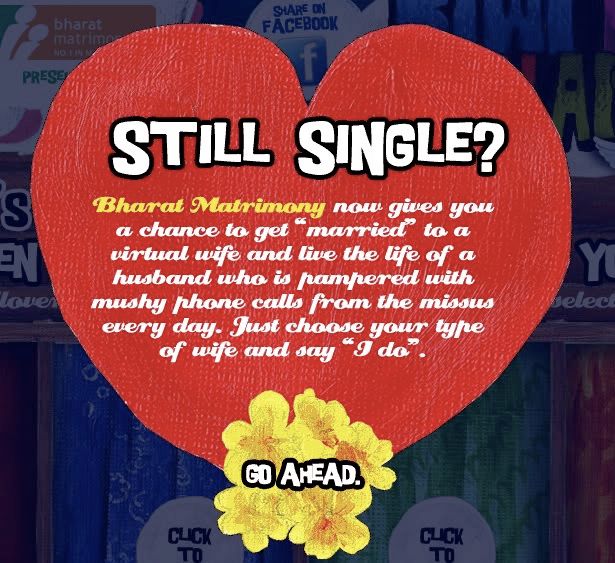

This is a truly obnoxious website that includes some pretty dumb sounding autoplay sound effects, and an entry screen that looks like this:

The Deccan Chronicle describes the four “virtual wives” offered to interested men, beginning with two fairly “traditional” types who embody conservative cultural values, before moving on:

While these two characters would be clearly identifiable for men of older generations, it is the other women who offer the most revealing insights into the changing characteristics of modern Indian womanhood.

Milli Chulbulli (Milli Naughty), 21, is an excitable secretary in a multinational firm with a life that revolves around shopping trips, neighbourhood gossip, and an addiction to television soap operas.

Finally, the website offers a chance to hook up with Shalini Sheherwali (Shalini From the City), an ambitious 26-year-old banker.

An independent, tech-savvy woman who purrs, ‘we’ll totally connect, honey!’, Shalini Sheherwali loves shopping online and loathes soap operas.

What I want to know is whether Bharat Matrimony is planning on offering “virtual husbands” any time soon…and if so, what stereotypes they’re going to, um, embody.

Suggestions?

India Indian music Jazz music Personal: ektaal form musical conception

by Warren

1 comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Some Thoughts on Rhythmic Cycles and Form

In late 1994 I was invited to give a lecture-demonstration on “world music” to a local cultural society in Pune. I talked about the similarities and differences in structure, conception and aesthetic values between, principally, Hindustani music, Ghanaian music and Jazz (since these are the musics I know best and love most); Vijaya and I demonstrated some ideas and patterns from these idioms, and I played a lot of examples from our collection.

For instance, I wanted to demonstrate how a jazz standard is used as the starting point for improvisation — so Vijaya sang “Body and Soul,” accompanying herself on guitar, and then played Coleman Hawkins’ version, which seemed to go over big.

Lecture-demonstrations are hard to predict, and the fellow who’d arranged this one had invited quite a few of his Hindustani rasika friends. For the most part they listened carefully, nodding appreciatively and making sage remarks sotto voce during our singing. Toward the end of the two-hour program, I started taking questions, and P______ B_______, an elderly vocalist, stood up. His question went more or less like this:

“All of these examples you have played us, they are all in medium or fast speed. Isn’t it true that only in Hindustani music do we have the vilambit tempo?”

This was another manifestation of the “only in India” concept, and as with all such, an answer requires considerable care in order to avoid either error or offense.

I asked him: “When you listen to a khyal in vilambit ektaal, do you actually count beats so slowly? One every five seconds?”

Immediately there was a corrective tumult. Nobody, it seemed, wanted me to believe that they really felt a pulse that glacial; several people fell over themselves in their eagerness to disabuse me of my misunderstanding, and began reciting the rhythm syllables of a vilambit cycle, showing me its internal subdivisions.:

Audience members: “No, no! Of course not — each beat has divisions, like te — re — ke — ta —…”

Warren: “So in vilambit ektaal, each beat is actually a larger unit, not a pulse you actually feel?”

Everybody agreed that this was so.

Warren: “So, a vilambit ektaal cycle is basically a kind of framework that forces the singer to organize his ideas in time, and fit his improvisation to the structure?”

Audience members: “Yes, yes, exactly!”

Warren: “But somebody who knew nothing of Indian music could listen to a vilambit ektaal piece, hearing only the subdivisions, and might not understand how the larger structure is outlined?”

Also yes.

Warren: “This is exactly what happens when you listen to our jazz pieces. In much music of the jazz tradition, there is a basic laya, which moves at a comfortable tempo and is maintained by the drums — and there is another rhythm, which moves much more slowly, and is maintained by the piano by changing harmonies according to a preset structure. Because you are used to hearing the large structure played by the tabla, you find it difficult to understand a large structure outlined by a totally different instrument.”

Well, the dialogue went on and on, and I’m not sure if I convinced anybody. After all, they sure didn’t hear any large structure in Hawk’s “Body and Soul!”

But the point I’m getting at is that all musical cultures have some way of organizing their performances in larger time-frameworks, and that we won’t find them by looking (or listening) where they’re not. Both khyal singing and traditional jazz of Hawkins’ ilk rely constantly on large-scale structures; the first articulated by tabla, and called the tala, the second articulated by piano, guitar or other harmonic instrument, and called, well, “the form.” Western musicians have adopted the generic term “form” to denote any structural constructs which guide a performance over time: “Repeat the first four bars of the A section under the sax solo, but play the bridge straight through” is a statement of form, as is “When the minuet begins, let’s remember to keep the tempo steady until we begin the decelerando at bar 37,” as is “Hey, let’s have a couple of choruses of guitar solo!”

In singing a khyal, by contrast, the form is the rhythm, writ large. Note the following example, and note it well, for it embodies a crucial principle:

Ektaal is a pattern of strokes played on the tabla; the same strokes, played in the same order, over and over and over. In fast and medium tempi, ektaal is a pleasant 6-beat or 12-beat groove, very catchy, easy to follow, each beat perhaps a third or quarter of a second; I just listened to a performance of madhya (medium) ektaal in which each complete rhythmic pattern took around four seconds to complete. When it’s performed in vilambit, however, ektaal’s drum strokes now occur once every four or five seconds — each cycle taking perhaps just under a minute!

A groove slowed down by a factor of twenty becomes an important form for improvisation in khyal. Now that’s an expansion of time!

India Indian music music Personal vocalists: obituary

by Warren

31 comments

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Bhimsen Joshi, 1922-2011. R.I.P.

At 8 AM on Monday the great Hindustani vocalist Bhimsen Joshi died in Sayahadri Hospital in his home city of Pune. He was 89, and a few weeks shy of his 90th birthday.

One of the most celebrated musicians of the twentieth century, Pandit Joshi was known as an impassioned and technically brilliant singer whose voice could execute anything that came to his mercurial and visionary imagination. His renditions of the traditional ragas of Hindustani music were filled with unexpected twists and turns, and he excelled at the expression of emotional nuance; his uniquely recognizable voice seemed to have its own built-in echo chamber. His last public performance was in 2007, sixty-six years after his stage debut at age 19.

Originally from a small town in Karnataka state, he ran away from home at age eleven, searching for music. more »

environment India: agriculture Assam tea

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Year 2, Month 1, Day 2: The Gypsy Woman Told Me…

The Times Of India notes that the tea plantations of Assam are reporting short crops…and flavor changes. The growers are attributing this to climate change. Why not? It makes a good hook for a letter.

The effects of climate change and the greenhouse effect are now beginning to be felt everywhere humans live and farm the land. Long predicted by climatologists, the problems attendant on planetary atmospheric warming have arrived. The changes reported in Assamese tea production, not to mention the unwelcome alterations in flavour reported by growers, are localized symptoms of a worldwide problem. While a specific example of extreme or unusual weather cannot be attributed directly to global warming (because that’s not how climate science works), the evidence is irrefutable: a warmer atmosphere makes weirder weather increasingly likely — more droughts, more floods, more “once-in-a-century storms” occurring every few years. It appears that scientists’ predictions match what Assam’s tea leaves are saying: humanity is facing an unimaginably different and difficult future, even if we change our ways immediately. And should we fail to make those changes, it’s going to be a bitter cup indeed.

Warren Senders

environment India: Cancun polluting industries

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Month 12, Day 18: Homeopathic Solutions for Climate Change?

Sunita Narain, the Director of India’s Centre for Science and Environment, is less than thrilled about the Cancun accord.

The first agenda before Cancun was to decide on how much the industrialized countries – primarily responsible for this global problem – would cut. The target discussed at the Bali conference in 2007 was a reduction of 40% over 1990 levels by 2020. So, tough decisions were needed at Cancun.

The Cancun deal has been struck by letting these countries off the hook. There are no targets. Instead, it has been agreed that now these countries will take action based on what they “pledge” to do. Take the US. If the target was being set (as was decided in Bali) on the basis of its contribution to the stock of gases already in the atmosphere, then it would have to reduce 40% below 1990 levels by 2020. Now, US has “pledged” that it will reduce zero percentage points in the same period. Cancun legitimizes its right to pollute. It is no wonder that it worked hard to stitch the deal. It is no wonder that western media and leaders are ecstatic about the breakthrough. It is their victory.

What Cancun has done is to shift the burden of the transition to the developing countries. If the combined pledges of the developed world are compared to those of the developing (including India’s commitment to reduce energy intensity by 20% by 2020) then the sell-out character of the deal becomes clear. The industrialized countries, who till now were being asked to take on the burden, will end up cutting less emissions than the developing world. They cut roughly 0.8-1.8 billion tonnes, against developing country pledges of 2.8 billion tonnes.

She has a point.

As an American citizen, I heartily concur with Sunita Narain’s assessment of the Cancun agreement. The inability of the world’s biggest polluters to take responsibility for the disaster they have fostered is a moral outrage, an ecological nightmare, and an economic travesty. What does it say about our system of values that wealth is so strongly correlated with pollution and environmental destruction? Of course, there are reasons for optimism in the fact that an agreement of any sort was reached at all; the current accord is assuredly better than the contentious travesty that was last year’s Copenhagen summit. But it’s hard not to feel that we’ve slapped a tiny bandage on a huge wound; when humanity confronts a threat that may well destroy the lives of billions, we need robust, concerted and immediate action to end our dependence on fossil fuels if our species and our civilization are to survive.

Warren Senders

India Indian music music: agra gharana genius khyal

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Dinkar Kaikini

Performing Raga Komal Re Asavari, with Sheikh Dawood Khan on tabla:

I enjoy his singing so much. The raspy and expressive voice always carries me along on the surging flow of imagination.

environment India: climate change India

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

Month 11, Day 20: Doin’ The Subcontinental

The San Francisco Chronicle runs an AP story on the likely effects of climate change on India:

A new report says India could be 2 degrees Celsius (3.8 F) warmer than 1970s levels within 20 years — a change that would disrupt rain cycles and wreak havoc on the country’s agriculture and freshwater supplies, experts said Wednesday.

More flooding, more drought and a spreading of malaria would occur, as the disease migrates northward into Kashmir and the Himalayas, according to the report by 220 Indian scientists and 120 research institutions.

Saturday’s letter was written mid-morning on Friday; I am getting ready to fly out to Madison, WI to do a lecture-demonstration on Indian music tomorrow, so I won’t have time to write later today.

As we look towards a future in which global warming alters coastlines, sea levels, storm intensity, monsoon patterns, and the availability of groundwater, it’s painfully evident that the Subcontinent is going to be battered as never before in its long history. A drastic change in any one of the factors listed above would be enough to trigger profound effects; when they’re all happening at once, we’ll get a slow-motion disaster that probably won’t end during our lifetimes or the lifetimes of our children. And, of course, it’s not just India; it’s all of us. The upcoming summit in Cancun is crucial for the world’s survival in the coming decades, but you’d never know it from the discussion of the issue in this country. Now that the party of denial assumes the majority in the House of Representatives, the rest of us will just have to assume the position.

Warren Senders

India Indian music music: genius Mallikarjun Mansur

by Warren

leave a comment

Meta

SiteMeter

Brighter Planet

So Much Beauty

Mallikarjun Mansur, singing Ek Nishad Bihagada and Nat Bihag.